Leading Edge Forum has been conducting next practice research for CIOs and senior leadership teams for over 30 years. One of its latest reports focuses on today’s ever-more capable digital ecosystem which is becoming the underlying business infrastructure of our time. This emerging set of horizontal services, referred to by the LEF as ‘The Matrix’ is a deliberate nod to the iconic 1997-2003 film trilogy.

‘Our goal is to assess and explain the enormous progress now underway in a terminology which both senior business leaders and technology professionals can understand,’ says Richard Davies, MD at the LEF.

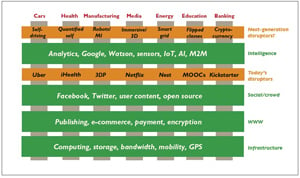

Just like roads, telephones and electricity in the 20th century, an ever-more capable digital ecosystem is becoming the underlying business infrastructure of the 21st Century. Whereas in the past each major industry sector had its own vertical ‘stack’ of processes and systems, firms must now leverage powerful ‘horizontal’ capabilities, used across many industries. These new capabilities are transforming many aspects of business and society, and will only get stronger over time.

In our research, we refer to this emerging set of services as ‘the Matrix’. While we could have easily used existing terms such as the internet, the web or the cloud, we believe that the metaphor of a ‘matrix’ best captures the growing friction and synergies between vertical and horizontal market forces. While ‘the cloud’ suggests something ‘out there’, like it or not, we are all part of the Matrix - a place where our virtual identities increasingly have a life of their own.

The Matrix is now challenging huge swathes of the global economy, this puts a particular emphasis on the need for leaders in large organisations to understand and leverage these capabilities, and in some cases to influence and contribute to them. On a cautionary note, as the history of roads, telephones and electricity suggests, major shifts in societal infrastructure often result in new industry leaders. Not every firm will make the transition to the Matrix-based future.

Click the image for larger version

In the past, most company business models were based on their own functional and process ‘stacks’. For example, major banks would have their own branches, data centres, credit cards, ATMs, CRM systems, loan approval processes, investment advisors and so on.

Increasingly the most interesting new businesses come from firms leveraging the green layers in the above matrix illustration.

Consider the way that Uber has taken advantage of public infrastructure - smart phones, cloud computing, global positioning services, mapping software and internet payment mechanisms. While Uber has initially focused on the market for taxis, it’s easy to see how it could eventually be woven much more deeply into areas such as home deliveries, car sharing/rentals, mass transit systems, and a wide range of social media and location-based applications.

These and other public horizontal infrastructure capabilities will continue to emerge, even though you didn’t ask for them. They are not waiting to be ‘sourced’ as alternatives to in-house provision, they are the building blocks of the future.

Value chains are becoming longer and profits are migrating

Businesses have increased in specialisation for decades. In the early days of the automobile industry, the Ford Motor Company didn’t just have factories for making cars. It owned steel companies, shipping firms and even rubber plantations. No-one does this anymore, and the global automobile industry now consists of hundreds of thousands of specialised firms. The computer industry - once dominated by the vertically integrated IBM - has followed a similar path.

While industries such as banking, insurance, hospitals, pharmaceuticals and utilities have experienced less dramatic change, they too are becoming more focused. Our research shows that roughly two-thirds of large firms believe they are becoming more specialised over time, and only about 5 percent less specialised.

On the other hand, the leading Matrix firms themselves continue to diversify. Apple has moved into TV, watches and cars; Google into robots, cars and retail delivery; Facebook into news, money transfers and even drone-based WiFi; Amazon and Jeff Bezos into just about everything. Perhaps the best way to view today’s incumbent specialisation is through the lens of their shrinking horizons as the Matrix expands ever more ambitiously.

The Matrix is affecting business value chain evolution in two other important ways. First, value chains are being lengthened - from the customer experience at one end to Big Data analytics at the other, with all manner of specialised services in between.

In most sectors today, the customer is actively part of the value chain - posting reviews, advice and suggestions, personalising technologies, continually learning. This is why we put so much emphasis on the importance of customer co-creation.

Less obvious is the fact that in a Matrix environment profit migration is the norm. Profits migrate to where there is either unique value or a dominant market position - think Intel and Microsoft in the personal computer market.

This means, for example, that Apple makes most of the money in the mobile phone and online music markets, as Uber does, and will, in taxi services. The potential for large-scale profit migrations in cars, healthcare, financial services and other industries is a major issue for business leaders.

Large firms often have a number of different business units. Whilst some units may be more profitable than others, most traditional firms have generally positioned themselves as full service providers. For example, in banking the strategy was to have products for a wide range of financial needs and cross-sell the customer into additional products.

But as we have seen, the Matrix is driving structural business change. As more and more Matrix firms emerge, the incumbents’ control over the marketplace, and their share of total value-add, is bound to shrink. Matrix firms typically target the most profitable elements of the business, forcing incumbents to compete on individual services and to unbundle their business models. Today, virtually every part of the value chain is in play.

The role of digital leaders

Dealing with the opportunities, threats and risks of working with the Matrix presents new leadership challenges for most executives in traditional firms. While management is generally aware of the importance of digital technology, relatively few executives have had direct experience in this area.

With new capabilities appearing virtually every day, ignoring the Matrix is not an option. Today’s leaders need to embrace the fact that the Matrix is a powerful, unruly force that they cannot control and whose movements cannot be predicted. Executives should ask the big, simple questions:

- What is the ‘do nothing’ future situation likely to be?

- Who are the new disruptors and where will they seek to enter our markets?

- What are the major scenarios that might become reality?

Management needs to develop an intuitive ‘feel’ for the Matrix, and this can only be done by getting out of the office and engaging with key Matrix players. Executives should spend time networking in digital circles and seek to understand their industry ‘outside-in’. They should also be trying to hire digital leaders who have lived in and absorbed the Matrix culture.

Just as it would have been folly for business leaders in the 1920s to dismiss the revolutionary inventions of that time, so it is unwise for today’s business leaders to see the relative calm in day-to-day operations as a reason to ignore the extraordinary digital progress that is now under way. The Matrix will only become more powerful and all-encompassing in the years and decades ahead.