The Computer Arts Society, founded in 1969 as a BCS Special Interest Group and still going strong in its 51st year, has seen the ebb and flow of interest in various digital artforms, writes Dr Nick Lambert, Chair of the Computer Arts Society BCS SG.

These different incarnations of digital art - from the plotter drawings and early robots of the 1960s, through the networked art of the nascent internet in the late 1990s, to virtual reality-based media of the 2010s - had momentary breakthroughs into the wider artworld.

Some mainstream artists, including Andy Warhol, Richard Hamilton and David Hockney engaged with digital imagery on differing levels of seriousness. This recognition has been the cornerstone for subsequent artists working in the medium of software.

Despite the acknowledgment of the ‘creative industries’ as an increasingly digitised field, there was not really a moment when the concept of digital art ‘clicked’ with the general public until the interest sparked by NFTs brought the area some much-needed attention.

The art of looking...

On 13 April 2021, at the height of the first wave of enthusiasm about NFTs in the arts, the Computer Arts Society hosted a panel session featuring the digital artists Fabrizio Poltronieri, Alex May and Sean Clark, with curator Irini Papadimitriou, to discuss the opportunities afforded and problems posed by the rapid growth in NFT-based digital art.

These NFTs, or non-fungible tokens, are not artworks in their own right; rather they are: ‘digital assets that represent a wide range of tangible and intangible items, from memes and collectible sports highlights to virtual art and furniture. Each one is individually identified on a blockchain, the most popular being Ethereum.’

The NFT concept emerged as a way to use Bitcoins to denote different types of assets in a hypothetical system of ‘Colored Coins’ suggested by Meni Rosenfeld in December 2012. He suggested that one use case would be ‘Decentralised digital representation of physical assets: [...] over time, a consensus could arise that a token is commensurable in value to some traditional currency or commodity [...] This will allow digitally holding value tied to physical assets.’ Then in 2014, the CEO of Glitch, Anil Dash and digital artist, Kevin McCoy, made a type of ‘monetised graphics’ that were a means to verify digital art.

This addressed a key problem that has always bedevilled art made using software: in most cases, it is replicable and not unique as such; therefore, it has been sold in editions like traditional prints but lacks the cachet of a unique physical work of art. From the viewpoint of art sellers and collectors, this poses an issue in terms of the uniqueness of such works.

Blockchain offered a way to declare and transfer ownership of digital assets. The ‘Proto-NFT’ that Dash and McCoy developed was intended to solve the issue of digital images and videos being shared without any attribution or compensation to the artists involved. As Dash said: ‘Technology should be enabling artists to exercise control over their work, to more easily sell it, to more strongly protect against others appropriating it without permission.’

The problem with digital

Although this was more a concept than widely-used solution, the idea surfaced once more following the emergence of the Ethereum platform. This began with Canadian developer Vitalik Buterin, who was looking for a platform enabled the building of decentralised applications.

With the assistance of other founders, the Ethereum Foundation was set up in 2014 with its own scripting language based on a paper by Gavin Wood and created ‘smart contracts’ which would execute software under predetermined conditions.

The flexibility of this decentralised concept attracted a diverse range of developers and, in 2017, John Watkinson and Matt Hall created 10,000 unique cartoon characters, or Cryptopunks, which could be initially claimed for free, using the Ethereum wallet.

The interest these generated showed the need for an Ethereum standard for NFTs and a standard called ERC721 was developed to enable NFTs to represent these assets. Shortly after it was implemented, Dieter Shirley released his CryptoKittens - a game about breeding virtual cats, which are NFTs to be traded. This was the first major success of the NFT concept.

Before this upsurge of interest in NFTs, the London-based digital art collective, Furtherfield, who have long been key players in online art, put together a book called Artists Re:Thinking the Blockchain in 2017 that was well ahead of the curve.

Collecting together some of the major critical voices looking at different aspects of blockchain’s impact on the arts, the book engaged with launches at FACT in Liverpool, London, Edinburgh, Berlin at Transmediale and Amsterdam. It pointed towards the potentials for decentralisation.

A (virtual) licence to print money?

The emergence of NFTs as a means of selling digital art can be tracked by the rapid curve traced by Beeple, aka Mike Winkelmann, who began putting his work on the Nifty Gateway auction platform in late 2020. A creator of futurist and dystopian scenes that borrow heavily from established sci-fi culture, Beeple also has a more satirical edge using politicians and celebrities.

For you

Be part of something bigger, join BCS, The Chartered Institute for IT.

His work, The First 5000 Days (consisting of daily images gathered over 13 years from 2007 and collaged together) was auctioned by Christie’s in an online sale for $69 million. That sale alone put Beeple into the top three living artists in terms of value, just behind David Hockney and Jeff Koons.

The flurry of commentary that followed focused on a number of issues: the rapid emergence of this new process and its viability (or indeed desirability) as a new vehicle for selling art; the aesthetic and cultural questions raised by Beeple’s sudden climb to prominence (although he already had a large fan base of around 2.5 million followers on social media); and the likelihood that NFTs would continue to generate such astounding prices.

In this regard, it is notable that the purchaser of the work, crypto-currency investor Vignesh Sundaresan, or ‘MetaKovan’, paid for it using 38,000 Ethereum; and equally notable that Beeple swiftly converted this into its equivalent cash value. This led to another debate about how much more he would have gained if he had held onto the rapidly-rising cryptocurrency. Or, indeed lost, given the volatility of the currency.

The concept and value of ‘rarity’

Having generated a great deal of light, heat and innumerable articles by technologists, artists and collectors - many of them aggrieved about the sudden encroachment of digital objects into the rarefied world of art sales - there is now a feeling that the air has escaped from the NFT market. Headlines that breathlessly announced the most expensive NFTs ever sold (including Twitter cofounder Jack Dorsey’s first tweet, sold for $2.9 million) now revel in the doom of collapsing NFT sales.

It certainly appears that the general slide in cryptocurrency trading, which is partly in response to Chinese regulation of the ‘mining’ process that generates new tokens, is also hitting the NFT market. Certainly, the peak of demand for NFTs was around 9 May when they reached $176 million over 7 days; that figure is now down to $8.7 million as of 15 June.

Apart from the fall in cryptocurrencies, the saturation of the NFT market occurred as more people got into the NFT medium and new projects such as CryptoPunks’ ‘MeeBits’ were launched.

For sceptics, this was vindication of the ephemerality of the NFT craze and proof of its symbiotic relationship with the fortunes of cryptocurrencies. For instance, the director of the UK Hackspace Foundation, Jonty Wareing, posted a series of tweets on 17 March where he traced the references from a typical Beeple artwork on Nifty Gateway.

The NFT token pointed to a JSON metadata file hosted on Cloudinary via Nifty Gateway’s servers. If, for any reason, the host went bust, the token would then be worthless because it pointed to nothing. Not only were some NFT buyers already reporting that their files were no longer hosted, but Wareing made the prediction that ‘It is likely that every NFT sold so far will be broken within a decade.’

Apart from scepticism about the longevity of the technology itself, there were others who saw the business model as primarily a question of using cryptocurrency profits to fuel yet another asset bubble; indeed, many of the bidders on the Christie’s auction were said to be millennials who had profited from the rapid rise in crypto values and were able to leverage their early entry into this market.

Is it worth the energy?

The most trenchant criticism of NFTs has been focused on the impact of the ‘proof of work’ aspect of the Ethereum blockchain which hosts the transactions of most art NFTs. The whole process has been condemned as wasteful by several artists who are otherwise supportive of digital art, including Memo Akten, whose essay ‘The Unreasonable Ecological Cost of #CryptoArt’ fired a salvo against NFTs in December 2020.

He produced a website to estimate the carbon footprint of CryptoArt NFTs as a result of blockchain-based transactions relating to the NFT, so these are only the calculations that keep track of sales and activity. Akten estimated on this basis that one artist’s multi-edition NFTs are equivalent to 260 megawatts per hour, or boiling a kettle 3.5 million times. The perception that this activity is especially ecologically damaging has made some artists avoid NFTs altogether.

Perhaps, then, the collapse of cryptocurrencies and NFT sales means that the panic is over and those who felt most threatened by the emergence of this new approach to authenticating items and transactions will be quietly pleased to see their values crash.

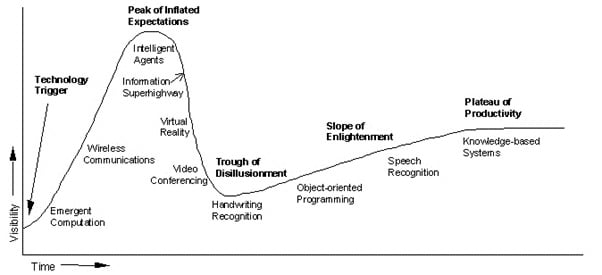

However, there should not be a Luddite reaction to the blockchain concept. Rather, there should be more transparency in terms of the way NFTs are promoted and fewer hyperbolic claims for this technology. It is notable how the sudden enthusiasm for anything ‘crypto’ resembles those made for the internet over 20 years ago.

Again, although this emerged suddenly in the eye of the general public, it was the result of a slow evolution that dated back to the 1960s. In the case of the web, it was the promise of hypertext put forward by Ted Nelson, that led to the pragmatic implementation of his ideas by Tim Berners Lee; then the rich media encouraged by Web 2.0; and now the promise of a new kind of digital ecosystem underpinned by blockchain.

Internet inventor sells www source code

At the end of June 2021, Tim Berners-Lee sold an NFT of his original source code from 1991, which was used to create the World Wide Web for $5.4m (£3.9m). The auction, which was handled by Sotheby’s, included several items besides the code itself, not least a physical poster and a letter from Berners-Lee outlining his thoughts on the process of inventing this novel technology.

In the 31 years since Berners-Lee’s own invention became a vehicle for commerce, commentary and art of all kinds, other digital technologies have risen, declined and re-emerged. The Gartner Group’s Hype Cycles have been released every year since 1995 and this first one has several entries that look familiar over a quarter of a century later:

Based on this cyclical development, it may be that NFTs will eventually emerge in a very different way to the speculative role they currently occupy. Rather than being static tokens for collectors, they will have a dynamic role in the virtual worlds that are gradually developing in several different but interconnected ways.

One of the most interesting is the Omniverse put forward by graphics card industry leader Nvidia. NFTs might represent a fundamental shift if considered with other advances in associated areas such as AI, augmented reality and metadata.

Ushering in a new immersive world

Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang, is most enthusiastic about the idea of a collaborative environment called Omniverse, where engineers can work on designs in a virtual environment.

In these metaverses, you’ll spend time with your friends. You’ll communicate, for example. We could be, in the future, in a metaverse right now. It will be a communications metaverse. [...] There will be AR versions, where the art that you have is a digital art.

You own it using NFT. You’ll display that beautiful art, that’s one of a kind and it’s completely digital. You’ll have our glasses on or your phone. You can see that it’s sitting right there, perfectly lit and it belongs to you. We’ll see this overlay, a metaverse overlay if you will, into our physical world.

In Huang’s overarching vision, NFTs will be part of a larger digital ecosystem and provide authentic digital objects to populate these online worlds. This links seamlessly with representations of real-world buildings, or digital twins, that replicate their functionality and an underlying sense of organisation that makes the Omniverse similar in its appearance and relations to the physical world or ‘real world’ usefulness, in terms of its affordances and digital tools for professionals.

In this regard, the use of NFTs to anchor otherwise ephemeral digital works to the simulated universe provides an interesting paradox: authenticating a work that only exists in a specific simulation of reality.

Plenty of distance left to run

The promise of computer-generated art, as articulated by the Computer Arts Society at its inception in 1969, was a vision of democratising the arts and increasing their scope through computation. Six decades later, with the world increasingly existing online, the NFT could provide a channel for this vision to be realised.