History has a habit of repeating itself if we don’t study the past and learn from it, Professor Steven Furnell FBCS tells Martin Cooper MBCS. And this maxim holds true, even in the world of cybersecurity.

‘We’ve always needed some sort of security for our computing technologies,’ says Professor Steven Furnell, ‘What’s different today is quite how much of it we need, across so many devices and services.’ Furnell is Professor of Cybersecurity in the School of Computer Science at the University of Nottingham and also chairs the related Technical Committee within the International Federation for Information Processing.

‘My interest in cybersecurity is framed around the point where people and technology meet,’ he says. ‘I’m interested in how people understand and relate to cybersecurity... How people use cybersecurity.’ Furnell has been working in security for almost 30 years - long before it was actually called cybersecurity. However, he also has another technology interest that goes back even further, namely a passion for retro computing.

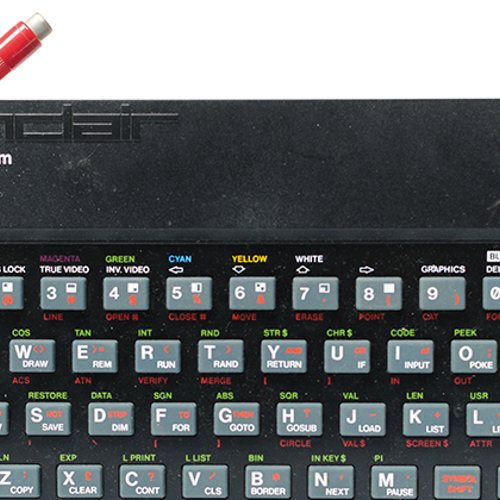

‘I started off with a Sinclair ZX Spectrum,’ says Furnell, ‘But, within a year or two, I was interested in what came before it. So, I got my hands on a Sinclair ZX80. That’s where it all started for me. When I began to earn some money, I started to see all the things I couldn’t have as a child appearing in second-hand shops and car boot sales.’

Furnell’s collection - which now extends well beyond a pair of Sinclairs - forms the basis of the South West Retro Computing Archive, housed at the University of Plymouth (where he previously worked and maintains a visiting affiliation).

‘We wanted to do something that gave some identity to our part of the building. We bought some glass cabinets, I had some retro computing bits and pieces laying around that were initially just put in there as a holding position. The display took on a life of its own - people seemed interested. And so, the collection grew in a much more formal way.’

As a collector of retro technology, Furnell believes there is much to be learned from cybersecurity’s past. Brain, the Morris Worm, boot sector viruses, the AIDS Trojan - these incidents, he believes, have a positive value for those willing to learn from them.

‘It’s worth understanding how these pieces of malware came about,’ he argues. ‘We can learn by understanding how and why these viruses were so successful. ‘The Morris Worm,’ he says, ‘is a prime example of lessons from the past.’

The Morris Worm attacks

The Morris Worm was launched on 2 November 1988 and turned out to be rather too successful for its own good. After release, it quickly infected (some claim) around ten percent of the machines connected to the then much smaller internet.

Written by Robert Tappan Morris, a graduate student at Cornell University, the eponymous piece of malware was the first worm to be distributed by the internet. It also resulted in the first felony conviction under the US Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (1986).

‘The Morris Worm was motivated by curiosity and experimentation,’ Furnell explains. ‘Morris tried to exploit three known areas of vulnerability and found that they were ripe for subversion. It worked very successfully.’

The point, Furnell believes, is that cyber criminals have the same opportunities today, as many systems and networks have known vulnerabilities which can be patched but, critically, often aren’t.

WannaCry, 2017’s now notorious ransomware attack, fits into this category. ‘The patch had been available for certain platforms for a while,’ Furnell explains. ‘The problem was, the vulnerability affected different versions of Windows, including XP, which was way beyond end-of-life at that point. In the event, Microsoft did subsequently produce a patch to protect installations of XP as well.’ Despite this, he says: ‘The malware got its foothold where things hadn’t been closed off.’

Like Furnell’s collection of vintage tech, a 3.5in disc that holds the Morris Worm’s source code is displayed in a glass case - albeit in California’s Computer History Museum. The need to preserve awareness of old malware goes beyond displaying it as a curiosity though. There have been instances, Furnell says, where old malware has re-emerged, confronting today’s technologies with yesterday’s foes and attacks.

‘When you get a new strain of malware, you get lots of new variants too,’ he says. ‘People repurpose and extend the original code - giving it new properties, exploits and changes to the payload. Mirai, the botnet malware, appeared in 2016. A few years later, we had IoT malware that used Mirai code as its basis - so the code was living on in later variants.’

Make do and mend

Along with recycling old attack vectors and reusing existing code, cyber criminals also revisit vintage ideas and blend them with today’s technologies.

For you

Be part of something bigger, join BCS, The Chartered Institute for IT.

Back in the late 1980s, a piece of malware circulated that replaced the autoexec.bat file on DOS machines and used the changes to count how many times the PC had booted. When it saw the ninetieth boot, the malware encrypted all the files on the C: drive and demanded a ransom of $189 to release them. The malware became known as the AIDS Trojan and it is one of the earliest examples of ransomware.

Today, of course, cryptographic attacks are rife. ‘You’ve got more of the pieces in place which make ransomware possible and profitable,’ Furnell explains. ‘The AIDS Trojan… Somebody created a database that claimed to be about the AIDS virus and posted out infected discs containing the information. It was sent by postal mail to people on medical mailing lists. They found a ransomware demand, asking them to post money to a post office box in Panama. Not many people did and it was a costly endeavour for the perpetrator to buy and post all the discs.’

Looking at today’s ransomware attacks, Furnell says: ‘CryptoLocker, in late 2013, really marked ransomware’s resurgence. You’ve got the internet as the means of distribution, you’ve got cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin which you can use for payment… This means there’s less traceability. And, of course, ransomware now has a proven track record of success. That success encourages other criminals.’

Where technology leads, criminals follow

Cyber criminals work hard to exploit new technologies - but not all new technologies. Rather, they go after the right ones and - crucially - at the right time. Cases of mobile malware, for example, cropped up as early as the turn of the century. These attacks were often proof of concept exploits.

Picking up the theme of retro computing, Furnell recalls worried users of PDAs (personal digital assistants - vintage handheld organisers) fretting about viruses on their Palm Pilots and Windows CE machines. ‘Yes, some people had PDAs, but why would malware writers want to turn their attentions to them and away from PCs when they had so many vulnerable Windows users ready for exploitation?’ asks Furnell.

‘Devices or platforms become attractive to criminals when you have a significant userbase that makes them worth targeting,’ he says. ‘The tipping point for mobile devices came in around 2011, when Android had become popular. There were enough people using the devices and it was clear that the users weren’t protected against malware by default. At that point, you can see a significant rise in mobile malware strains.’

The key point, Furnell emphasises, is that criminals will begin developing malware and exploits for a new platform when that device has attracted a suitably large audience. And, if that audience is transacting financially through that new platform or sending personal data through that device, it makes the platform all the more ripe for exploitation.

Never mind the risk, here’s the benefit

This lock-step evolution of technology and the associated opportunities for crime presents the buying public with a double-edged sword. As buyers, we are understandably wowed by what new devices can do to improve our lives.

‘It’s natural that technology is sold as beneficial,’ Furnell says. ‘Nobody is going to market digital risk. But, people are accepting the benefit and not questioning whether there is a downside. However, I think we’re getting to a point where people are going to say: “Other bits of technology I’ve bought looked good at the outset and then problems and exploits became apparent later... Let’s wait for generation two or three”.’

Expanding the point, he says: ‘We’ve now seen plenty of evidence where, sometimes, providers and manufacturers have been very keen to be first to market to keep that advantage and so, security is not on [consumers’] shopping lists. Security, or the absence of it, isn’t something that’s going to prevent people buying.’

How many enemies within?

Hardware’s security can, to a degree, be improved by patching software. Vendors can and do make software upgrades available, which can plug known gaps and holes. The problem lies in understanding and appreciating what software patches are, why they exist and how to find and apply them. The whole business of keeping a modern connected household safe places a technical burden on the public.

Is it fair for manufacturers to expect us to be our own technical support departments? ‘Frankly, no,’ Furnell asserts. ‘There’s more that should - and can - be done to make technology usable for people and to make it apparent that [security] is a consideration.’

This invisible contract with manufacturers, where we take on maintaining and securing our devices, may even be more disorientating for people who have lived with technology. Consider your television: you’ll likely have owned several - each bigger and better than the last. And none will likely have needed security patching until you bought your most recent.

Smarter but not more secure

‘With the early generations of technology, [security] wasn’t relevant. I didn’t have to think about the potential for malware on my TV, nor the need to update it for security reasons,’ Furnell reflects. ‘It wasn’t on the network. It didn’t have that level of connectivity, yet those features have crept up on us. They are now a natural element of that sort of device. It’s more difficult to find a non-smart TV than a smart one... And they are not sold with a warning on the package that says: “This device needs regular maintenance and attention.” It’s different with something like a car - you’re used to the fact that it needs maintenance.’

The password isn’t dead

And it seems, despite all the gloss and sheen of modern consumer technology, most modern devices have one common security denominator: the password. Despite the march of Moore’s Law, the shift from HD to 4K and the dawn of 5G - our devices’ moats and portcullises are often still only as strong as the passwords

we create.

‘We’ve been predicting the death of passwords for almost two decades,’ Furnell reflects. ‘Things are getting better. We’ve got multifactor authentication and biometrics, but what’s the fallback when that doesn’t work? Our devices all drop back to a password or a PIN.’

Poorer providers are leaving their users to understand the difference between a weak password and a strong one. ‘There are sites and services that will accept a password that all the guidance tells you is bad,’ Furnell observes. ‘The top weak password - according to data - is still 123456. If the service isn’t doing any other checks, that is an acceptable choice. Of course, it shouldn’t be.’ Once more, manufacturers and service operators are placing a responsibility on users to be technically aware and competent.

Don’t look back in anger

So, how will tomorrow’s computer historians and retro collectors look back on today’s technology - technology that has so many possibilities and, as we’ve discussed, so many potential flaws?

‘I think they will be interested in our early ventures into smart devices. They’ll probably look back on the limited degree of integration and interoperability,’ he suggests. ‘I think, as we move forward, we’ll see the idea of your profile being the thing that transits between different devices.’

It may be, though, that tomorrow’s hardware collectors will have a sadder time than today’s retro fans. Barring hardware failure, a ZX Spectrum will work just as well today as it did 30 years ago - the main difficulty a modern user might have is buying cassettes and discs.

Today’s smart devices, however, rely on web services to bring them to life and when those are turned off, today’s hottest technology will be rendered lifeless.

Will tomorrow’s technology museums be places where we come to look at glass cases filled with moribund plastic cylinders, cubes and cuboids? Places that, sadly, never will light up when you say “Alexa”, “Okay, Google”, or “Hey, Siri!”

Visit the collection at www.retro-computing.org and by following @SWRetroComp on Twitter.

How to start a career in cybersecurity

‘Don’t get disheartened by lots of job adverts that ask for five or six years of experience and lots of certifications. There are lots of early career opportunities in cybersecurity.

Look at early career certifications - something like Security+ is a good way of getting up to speed with foundational aspects. Also, recognise what your skills are. CIISec - The Chartered Institute of Information Security - has a security-specific skills framework.

‘If you’ve got an interest in the area, measure your skills against the framework to help understand where you’re positioned, where would you like to head and what sorts of skills you’ll need to get to achieve that goal.

‘We use the labels cybersecurity or information security, but there are a whole range of roles and specialisms within these.’

How to make your cybersecurity CV stand out

‘Understand what you’re bringing to the table. If you’re coming in from, say, law, psychology, economics or business, recognise those subjects do have currency within the context of cybersecurity.

‘It’s not just about the technical aspects... It’s about understanding what cybersecurity is there to do… It’s about protecting an organisation. It’s about understanding data value and understanding people.’

How to step up to cybersecurity leadership

‘Understand where cybersecurity fits in to an organisation - the business and organisational contexts. It’s about having that wider, holistic view. It’s about being able to build the business case for cybersecurity.

Management, leadership and communication are important - being able to operate as a professional inside the wider organisation. You need to be able to have conversations about cybersecurity that don’t rely on everybody understanding the underlying technicalities. Be the cybersecurity Babel Fish!’