BCS has responded to a call for evidence from the Parliamentary Science and Technology Select Committee on the governance of Artificial Intelligence , and submitted its response on 25th November 2022.

Background

In September 2021 the UK government published the National AI Strategy. Included in the strategy was an action to consult on proposals to regulate the use of AI under certain circumstances. Those proposals are published here: ‘Establishing a pro-innovation approach to regulating AI proposals’. The BCS response to the consultation based on input from our professional membership can be found here. The key focus of the Science and Technology Select Committee is examining the government’s proposals to regulate AI. Hence, the BCS evidence to the Committee is derived from our response to the government’s consultation on those proposals. The following headings are taken directly from the consultation, with our response.

How effective is current governance of AI in the UK?

It is important to appreciate that Artificial Intelligence (AI) is still a set of nascent technologies. There are organisations in all UK regions struggling to build management and technical capability to successfully adopt AI.

Standards of AI governance in the UK are not uniformly high

Good governance of technology that impacts on people’s lives, whether that is AI or some other digital technology, leads to high standards of ethical practice and high levels of public trust in the way the technology is used.

Our evidence strongly indicates there is not a uniformly high level of ethical practice across information technology in general, and there is a low level of public trust in the use of algorithms (including AI) to make decisions about people.

Given governance of AI is often integrated within existing governance structures around data and digital, our evidence indicates there is not a uniformly high standard of AI governance across the UK.

Further details of BCS surveys

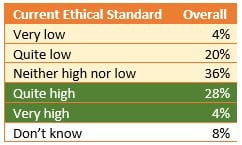

Our most recent survey of ethical standards in information technology had responses from almost four and a half thousand BCS members (see Table 1 for details) working in all sectors of the economy and at all levels of seniority.

When asked to assess the general standard of ethical practice in the organisations they worked for:

- 20% stated the standard of ethical practice was quite low

- 4% that is was very low.

- 32% of members felt ethical standards were quite high or very high.

Table 1: Results from survey of over 4,400 BCS members in 2018

Whilst it is encouraging that ethical standards were perceived to be high by almost a third of those responding, the responses also show a high level of variability overall, where a quarter of members reported low ethical standards.

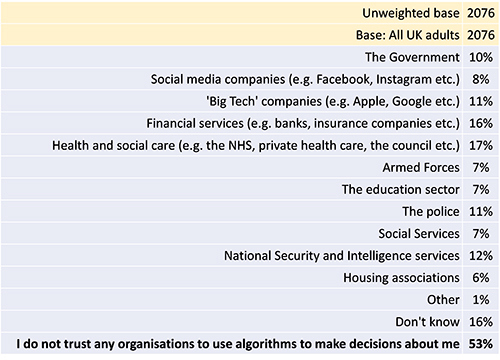

Table 2: Survey results to question - which, if any, of the following organisations do you trust to use algorithms to make decisions about you personally

For you

Be part of something bigger, join BCS, The Chartered Institute for IT.

In 2020 BCS commissioned YouGov to survey a representative sample of 2,000 members of the public across the UK on trust in algorithms.

The headline result from the survey was that:

- 53% responded ‘I do not trust any organisations to use algorithms to make decisions about me’

The survey question in full was: ‘Which, if any, of the following organisations do you trust to use algorithms to make decisions about you personally’ where the range of options to choose from is shown in Table 2 [NB - bold emphasis in the table was added only after the survey results were analysed].

What measures could make the use of AI more transparent and explainable to the public?

For the use of AI to be more transparent and explainable organisational governance should:

- Identify reasonably foreseeable exceptional circumstances that may affect the operation of an AI system and show there are appropriate safeguards to ensure it remains technically sound and is used ethically under those circumstances, as well as under normal circumstances.

- Evidence that organisations have properly explored and mitigated against reasonably foreseeable unintended consequences of AI systems.

- Ensure AI systems are standards compliant to enable effective use of digital analysis/auditing tools and techniques.

- Ensure auditable data about AI systems is generated in a standardised way that can be readily digitally processed and assimilated by regulators.

- Where necessary record the outputs of AI systems to support analysis and demonstration that outcomes are appropriate and ethical. Note, such recording may include personal data, thereby adding an additional potential data protection challenge. Without such recording and analysis, the organisation would not be able to demonstrate the appropriateness of AI outputs nor demonstrate such appropriateness to regulators. In cases where external challenge arises about potential bias/unethical decision making, such recording and analysis will be an essential part of verifying or refuting any claims.

- Treat data quality as a separate issue, particularly input data to an AI system. There is a risk that an algorithm tested as acceptable based on ‘good’ data may deliver unacceptable outputs when using ‘real world’ data (e.g. such as data containing invalid/missing entries or that are not sufficiently accurate). Note, consideration of undesirable bias should be seen as a key aspect of assessing real world data quality.

- Be capable of dealing with complex software supply chains that are distributed across different legal jurisdictions.

- Ensure transparency and appropriate checks and balances to address legitimate concerns over fundamental rights and freedoms that may occur if AI regulation is subject to legislative exceptions and exemptions (e.g. as in the 2018 Data Protection Act where there are exceptions for Law Enforcement and Intelligence Service data processing).

How should decisions involving AI be reviewed and scrutinised in both public and private sectors?

Properly reviewing AI decisions requires governance structures to follow the principles in Section 1. Decisions involving AI can then be properly reviewed as aspects of the governance structure. That is, the review of decisions made by an AI system, whether in the public or private sector, should focus on assuring that the proper governance structures are in place and governance processes are followed. That will mean decisions are based on data that is standards compliant and enables effective use of digital analysis/auditing tools and techniques to validate decisions.

Previous BCS studies highlighted that the use of an AI system should trigger alarm bells from a governance perspective when it is:

- an automated system that must process data streams in real-time

- uses probabilistic self-learning algorithms to inform decisions that will have significant consequences for people

- is used in such a way it is difficult to uncover how decisions are derived

- is used where contestability of a decision is not deterministic and

- ultimately decisions rely on some form of best judgment that requires understanding of the broader context

We call an AI system problematic when it has the above attributes.

Problematic AI systems describe a significant class of systems that would be very challenging to scrutinise or review decisions made by such systems. The overarching issue should be to prevent problematic AI systems being used to make decisions about people in the first place, which is best done by ensuring the governance principles described in Section 1 are always followed.

How should the use of AI be regulated, and which body or bodies should provide regulatory oversight?

The BCS view is that regulation should allow organisations as much freedom and autonomy as possible to innovate, provided those organisations can demonstrate they are ethical, competent, and accountable when measured against standards that are relevant to the area of innovation. Pro-innovation regulation should enable effective knowledge transfer, the sustainable deployment of new technologies, as well as stimulate organisations to embrace innovative thinking as core to their strategic vision and values, as illustrated in Figure 1.