As more technology converges, and people discuss the pressing worries of the day - data privacy, digital health records, cyber-bullying and more - there are deeper issues at play, which can be ignored in day-to-day life if one chooses to, but have great long-term consequences.

BCS’s stated goal of ‘making IT good for society’ aims to dig beneath the surface. Especially when we see large, powerful organisations behaving in a way that is typical for profit-oriented companies, but non-optimum for societal benefit. The general context of this conversation was summed up by Luciano in a quote from Norbert Weiner, in reference to any thoughtful person: ‘you need to be able hear yourself thinking...’ To really see the implications, or at least get a grasp on the potential implications, of any new technology, deep thinking is the key.

Even in academia, the speed of life has become rushed to the extent that there is constant churning of behaviour: publish the next paper, get the next grant, publish the next paper, get the next grant.

Whenever there is philosophy or ethics mentioned in IT, it always seems to gravitate toward a specific discussion - the trolley problem and how it is relevant to self-driving cars. Is this the wrong focus when we have a more immediate impact from the likes of Uber and Deliveroo apparently undoing years of hard-won employment rights? In the name of disruption…

Disruption is becoming an inflated concept and hence a useless word. It’s not news, to carry on being disruptive. You disrupt once, not continuously, because something has to be there to be disrupted in the first place. It is like discovering a new planet for the first time.

The landing happens once. Likewise, the wheel is discovered once and has an amazing history, and we are still discovering ways of using it, but that discovery is not going to happen again. So, digital disruption has happened, but focusing on it is now becoming a distraction.

Of course innovation is relentless. But the digital threshold has been passed. And it would be a pity if we were to look for new thresholds, focusing on fashionable and easy to grasp ideas, pop trends. The issues now are deeper and harder to understand and explain. On our new digital planet, so to speak, the new difficult task is colonisation. In short, the new challenge is not so much digital innovation but the governance of the digital.

For example, in ethics and IT, the trolley problem is a distraction. It is enough to read the Wikipedia entry to see that it’s simply a device to challenge ethical positions about secondary effects, such as whether to save the mother or the baby in a difficult pregnancy.

Thomas Aquinas covered this a long time ago... The trolley problem and similar puzzles are the equivalent of heads I win, tails you lose. It seems a joke, but it is irresponsibly distracting. The solution is not what to do once we are in a tragic situation, but to ensure that we do not fall into one. So the real challenge, in this case, is good design.

Meanwhile AI transforms the workforce as we speak. We have an approach of: ‘Do first, repair afterwards.’ The truth is that we need to look ahead, because at the moment employment law, the social safety net, and decent standards of living are bypassed. This leads to highly competitive environments where the lowest price wins, but few benefit.

For example, what if the gig economy was run by a cooperative? The benefits need to be shared with the larger community.

It seems the gig economy is being justified by the idea of ‘trickle-down economics’, but isn’t this a system that doesn’t work?

It is important where the money lands, but it is also important where it goes afterwards. The earnings of the likes of Apple are immense but they do not percolate, they do not go elsewhere. Capital tends to accumulate within small niches, it does not move.

This is a well-known phenomenon in complex systems, called local minima. Trickle-down economics takes the view that money behaves like water and goes from the big bowls at the top, which overflow into lower ones to spread the wealth. In practice, money behaves like a ball - and it stays in the top bowl.

The system needs a shake, and that shake often comes from taxation. The people who do the shaking, the politicians, should communicate that that is the way forward, and accept that they themselves may not be on the winning side when it happens. Unfortunately, here in the UK as well, the ruling class’ interactions with their schoolmates do not look promising. The situation is no better in the US, or in Italy, for example.

On the question of personal liberty, what should be our right to privacy versus the redrawing of privacy lines by information rich corporations?

We have already missed some chances to do the right thing. In the 1990s there was optimism: the Berlin wall, the end of Apartheid in South Africa, the end of the Soviet regime, Russia’s opening up, the Clinton administration, and so on. The internet was becoming part of the real world, and then gave rise to the web.

We could have adopted a more social model rather than an economic one; more analogous to public libraries and motorways, less to supermarkets and airlines. But in the end it was decided to shape the internet and the web as a market, for late regulation.

There were understandable mistakes, for example, the comparing of the web to any other utility, seen as pipes into the house. At the time the new infosphere wasn’t seen as a new space, but more like a utility like electricity, or a TV broadcasting service.

Today we live on the web. We used to login and logout, but now we don’t logout. For example, our mobile phones constantly record our geolocations, 24/7. We now live in what I call ‘onlife’ - a constant analogue and digital mix, both online and offline.

The second error was that politicians didn’t see that the space would be governed by whoever built it. Even the illusion that it is still a market, so that antitrust or customer services would regulate it, is often bypassed by new business models-based advertising. We are not customers, we are users. This is a gift that disempowers us. You can’t complain, let alone sue anyone, if you do not like a gift.

In this, the analogue world is kidnapped by the digital. To get a fridge we need to go to, for example, Amazon. The seller and buyer need to be there. The more we do this, the more the analogue (the fridge) needs to be there and submit to the logic of online marketing. Logically speaking it works, but socially, it is disappointing.

What exits are there now? Politicians sometimes debate whether we can go back. They ask if there a handbrake. The answer to both is no. Those exits are gone, and we cannot stop, but we can go forward more intelligently, more fruitfully.

I know it is risky, but I believe that, because today’s digital giants are so powerful, we need to bring them inside the decision room, visibly (transparency) and responsibly (accountability). We need to encourage corporate good citizenship. The view should be that a good, long-term, business plan goes hand-in-hand with good ethics in a good society. The cost is upfront, but the good is in the long-term results.

To achieve good results - no fake news, no terrorist-advertising fundamentalism, property rights protected, preventing hackers crashing systems, human rights respected, benefits shared and so forth - starts with ethical thinking. It requires a moment of longer term thinking that doesn’t pay in the next quarter, or next reshuffle. But this is the time for some real foresighted analysis and planning.

A good degree of altruism is doable. In business, it takes mature companies. This is slowly happening but it is not a reality in the digital world yet. For example, the gig economy contradicts it. Yet given the right efforts, we can set up frameworks that will deliver a better society. So, the real new innovation is governance. What if the government created a socially preferable, environmentally sustainable framework for the development of digital technologies? That would be news. That would be really ‘disruptive’.

So, in a world that moves as fast as it now does, can we fast-track maturity?

I think so. This is about the stick and the carrot. For example, companies make mistakes that they regret later. ‘Fail often and fail fast’ is no longer a good approach, when you have hundreds of millions of users affected by your potential mistakes. It is not affordable for business now because the cost is too large, the impact too deep.

Furthermore, some of our current mistakes could also be irreversible. And the market may not have the time to rectify errors and shortcomings. We need to be more mindful of the consequences of our innovation.

We need to create an environment where we minimise the chance that companies learn by making huge mistakes (recall what happened with the banking crises recently). We can do this using incentives and disincentives. The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), for example, is a huge stick, but it is a good platform. It may help prevention.

Consider that if it gets to a stage when only courts determine the viability of business models, then politics has not done its job. We must prevent mistakes and minimise their consequences, not retroactively try to solve them. And we must identify the future we want to realise, rather than just focus on the future we want to avoid.

BCS can play a significant role in all this, and add to its societal value. It could be more than just a professional association, it could also be a strong voice that contributes to social welfare in the digital space. Especially as we feel increasingly powerless as individuals.

What is your view of the higher profile thinkers who make remarks on the dangers of AI? - I am specifically thinking about the recent comments of Elon Musk and the late Stephen Hawking.

They are irresponsible, I have the least respect for that kind of scaremongering attitude. It’s crying wolf, unscientific, and clickbait. The empirical and scientific evidence we have and can forecast indicates that the dangers in AI are entirely human and human only. The rest is sci-fi and zombie movies.

On a personal level, some commentators make much of the constant distraction of connected devices, that they mitigate against long-form reading and hence deep thinking. What is your take on that view?

There are several stages in critical awareness. Stage one is that we just don’t know something, and so we need to explore; stage two is the acknowledgement that we have a problem and we need to define it; we now need to go to stage three - what do we actually do to address the problem? The fact that we have raised a red flag on our control is an important step, but I am tired of smart people focusing on problems, just denouncing, criticising, and analysing.

It’s been done, we must start writing the new chapter in which we identify solutions, good practices, helpful lessons from the past, and potentially successful strategies. This is difficult, much more difficult than just formulating questions. But it is what makes a difference. Imagine a GP who only raises questions and doubts. At some point you want to know not just what the health problem is but what the cure may be.

We know that digital technology relies on attention management mechanisms. Websites are designed to encourage clicks. And adverts are the monetised part of the same attention management. There may be limited PR value in intellectuals screaming about it but, for researchers, this is not news, and the noise is even part of the problem. Stating the problem has become the solution. If you have an eating disorder, recognition is important but then it needs action. You must change your diet.

For this, three areas need to come together: education, corporate responsibility, and government. If it were only about personal education, the message becomes that ‘it’s all your fault’. The corporates’ excuse is ‘we just provide what people want’. And government can hide behind the mantra ‘we allow and enable the free market’. Each of these views pushes the blame elsewhere. We need long-term coordination and commitment.

How do we get out of that loop of excuses?

This is a big question, and goes to the root of the democratic system. There is a tension between democracy and business models, they don’t go hand-in-hand. We need to rethink both. The online business model, the ad-driven model, is not good. Likewise, in politics, saying: ‘The people have spoken’ because 52 per cent vote for a particular outcome is not really taking democracy seriously. It means that minority views are not protected, and that leads to populism.

In short, we need to rethink the 20th century. Because at the moment we are in a zero sum game but this is very far from inevitable.

Are there good examples of social policy or approaches we can garner from other countries?

Scandinavian countries are often indicated as progressive examples. But what we need to remember is that they are tiny, many have populations smaller than London’s. Size makes a difference to resources, complexity and organisational approach.

It’s like saying that because you can organise a good party for five people that you can organise a successful concert for thousands of people at Wembley stadium. So, I’m in two minds about pointing to specific examples because these are more proof of concepts than scalable solutions for every situation. Each community has its own peculiar features. It is not a good idea simply to import solutions from other contexts. What is important is to realise that in other contexts it is doable, it has been done, so it may be doable in our context too.

What can we do to increase thought amongst entrepreneurs before they launch world-changing, or at least society-changing, technology?

Self-regulation can’t do it alone. Take the example of the charge for plastic bags. Everyone wanted to do it, but no-one moved because no-one wanted to be at a disadvantage, and rightly so. What was required was legislation. Re-leveling the playing field by raising the standards for all. It worked, because all the supermarkets were required to do it at the same time, none of them had a first mover disadvantage; consumers were happy for it to happen because they understood the environmental issues; and government brought that all together.

In tech, the ideas of social responsibility could be brought together in a similar way. For example, BCS and TechUK, could go to the government, with a mandate from their members, and indicate that they are happy for the government to upgrade the rules. We can’t change behaviour until we agree and ensure that it is a common change, shared by all.

The Jesuit approach is relevant here: to resist temptation you don’t only use will-power, you actively avoid putting yourself in a situation where temptation is more likely to arise. So agreeing an ethical stance, and having some governing bodies presenting to governments the opportunity to make an ethical framework a matter of public policy, means that the new framework becomes the new standard for everybody.

Right now, a variety of mechanisms in different countries support tax relief opportunities for donations. The IT giants have already won at the game of capitalism, so one may incentivise the donation of a percentage of their vast profits to social benefit. And if all companies are required by law to invest in socially good initiatives of their choice, then the rules of the game change. It’s the acceptable 5p plastic bags across the board.

What would a Philosophy 101 primer for tech people contain?

Rather than a reading list, a short introduction could be about understanding some of the conceptual issues, about design principles and ideas, about how to build better societies.

For example: Pareto Efficiency is a principle of dividing a resource, whatever it is, in as satisfactory a manner as possible. For example, four people get each one quarter of a cake. The idea is to achieve Pareto optimality - to get the most satisfaction for the most actors. It can apply to computing power, money, cake, anything. If one of the four people gets more than of a quarter of the cake, then that is not optimal because someone is getting less, and we move from four satisfied people to three.

More generally, the goal is to allocate resources in the most efficient manner, by ensuring that one participant’s situation cannot be improved without making another participant’s situation worse.

Also, from game theory, there is the Nash equilibrium. This, again, is about acting optimally, when each participant in a game has no incentive to deviate from his chosen strategy once he has taken into consideration an opponent’s choice, that is, each participant tries to make the best decision possible, whilst also taking into account the decisions of the others in the game.

There are also valuable concepts in the Markov state of a system, a stochastic model describing a sequence of possible events in which the probability of each event depends only on the state attained in the previous event. Activity can be affected depending on whether it is a zero memory system, or not. For example, the ‘crying wolf’ game is not a zero-memory system, that is, it is not a Markov chain, because it is dependent on several previous activities. Actors behave differently because they remember how many previous instances of the pointless alarm have already occurred. Chess, instead, is a Markov-like game, because it does not require that kind of memory. You can walk into a room and start playing at any stage, just by looking at the board, and independently of whether you know which moves lead to that configuration.

In the philosophy of design, Kolmogorov complexity comes into play. When we look at “10101010101010101010” and at “78231658172923349129” we can tell that one is simple and the other is complex. This intuition is exactly what Kolmogorov complexity formalises. It measures the complexity of an informational object, like a string of numbers, by referring to the length of its shortest description in a given vocabulary.

For example, the first string is obtained by the description ‘10 ten times’, which is very short and can create very long strings. The second string is random and so its description is only provided by itself. This has applications anywhere there are digits, for example, in computer science to data compression, and has an impact on efficient use of resources.

I have been dreaming of collecting similar principles in a short book, something like 20 conceptual tools to help you understand the world better.

What about personal responsibility? Our previous CEO used the example of architects - that they had the mandate through their qualifications to refuse to, say, build a bridge if they knew that it would be unsafe. In technology, these considerations don’t seem to be as strong.

The engineering of bridges is well known, so architects can make ethical decisions more easily; but IT systems are a new art. We are still learning the hard way to establish parameters and standards. I think we will get to the same stage of maturity soon.

This area needs more research to understand what goes right or wrong at the moment, to compare with existing knowledge and analyses till standards emerge. Socially-sound IT-building is not a book that exists yet. We need to encourage socially preferable behaviour.

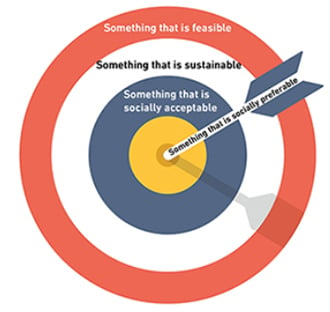

I have been working on a model for that, where we can assess social maturity and organisational maturity with an analysis of a nested set of options:

In the plastic bag case, for example, we can clearly see that it ticks all those boxes, with social preferability being the ultimate goal.

Tech often worries about number one, acknowledges number two and is satisfied with number three. We need to move digital innovation into number four, with rules that are self-reinforcing through virtuous cycles.

For example, if the population of a country sees its tax money spent well, they are more likely not to avoid paying taxes, which leads to a better country, potentially with lower taxes and so forth. But if they see poor services, even the taxes they do pay look onerous. They will try to avoid them, leading to a more exacerbated taxing regime, which reinforces the vicious circle of avoidance, and so forth.