One in ten IT roles is an analyst1. Most areas of technology have analyst roles; from cyber security analyst to UI analyst, business analyst to network analyst, test analyst to data analyst. What is the implication of this suffix ‘analyst’ and what do these roles have in common?

What’s in a name?

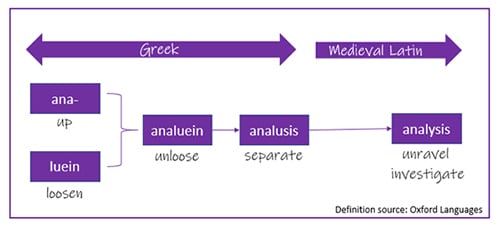

Looking at the origin of the word ‘analysis’ gives clues to the core of the analyst role. The aim of analysis is to loosen things up, break down to the simplest parts and unravel in order to understand.

The role of the analyst, therefore, is to define the area of focus, select one or more appropriate methods, obtain information, examine the findings and present the results. This is a repeatable process for any area of technology, for any type of analyst. This does not mean that analysts are completely interchangeable. Each step of the process often requires years of training and experience, which is unique to the area of focus. For example, the range of ‘appropriate methods’ would look very different between business analysis and network analysis.

Four types of analyst?

Analysts are often type-cast as quiet, methodical and studious. Good analytical skills can be coupled with a wide range of other personality traits, and the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator® (MBTI) provides a way of thinking about different preferences and traits. Whilst the framework has limitations and vocal opponents, any approach which encourages self-awareness and introspection can have value for individuals. 16personalities.com has categorised the 16 MBTI types into four groups - and one them is called ‘analysts’.

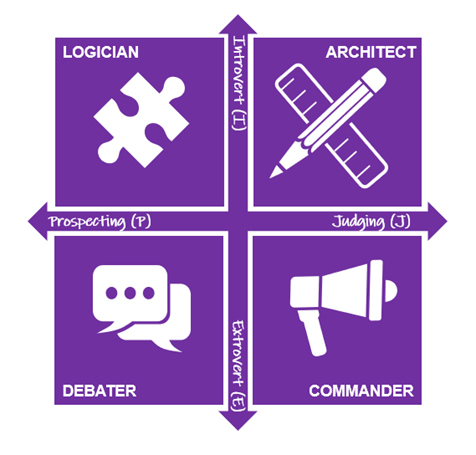

Interestingly, it is not ‘introversion’ that the four-types of analyst have in common. They have created the group by linking the traits ‘Intuitive’ (N) and ‘Thinking’ (T), suggesting that what makes someone analytical is (N) open-minded and curious and (T) prioritising logic over emotion. On top of these basic ‘analyst traits’, people can be either Introverted (I) or Extroverted (E), and either Judging (J) or Prospecting (P). This gives rise to four possible ‘types’ of analyst.

- Logician (INTP): Characterised by precision, invention and honesty.

- Architect (INTJ): Characterised by a pursuit of knowledge, independence and determination.

- Commander (ENTJ): Characterised by leadership, decisiveness and perseverance.

- Debater (ENTP): Characterised by enjoying intellectual challenge, quick thinking and confidence.

Whilst many people in analyst roles will have personality types outside of these four, it gives an interesting frame of reference for the behaviours we expect from ‘analysts’. Some analysts come up with limitless options and wish to debate the pros and cons with anyone who will engage (and if there is no one to engage with, in lengthy documents!) while others reach quick decisions and find it difficult to move away from them if things change. Some analysts prefer to work alone, others need colleagues to ‘bounce ideas off’.

Understanding that analysis is not just about being methodical and that there are a range of people that make ‘good analysts’, is imperative for getting the widest range of analytical perspectives.

Area of focus

There is a recurring trend to tie analyst roles to a particular technology or system such as ‘CRM analyst’, ‘ERP analyst’ or ‘XML analyst’. This type of focus makes it more difficult to determine what skills and methods are required by the analyst and removes business agility as technologies and priorities change.

Organisations may be tempted to define highly bespoke analyst roles that fit current organisational structures and naming conventions, for example ‘digital and e-marketing analyst’. This type of approach is inward looking to the organisation, not outward looking to the skills market and professional disciplines.

Organisations help themselves and the maturity of tech and digital professions by creating analyst roles which align to professional bodies and communities that are free from the names of systems.

The key to analytical success: curiosity

Whatever your personality, preferences or area of focus, there is one trait which has the capacity to make or break an analyst’s career and that is curiosity. Without curiosity, there is no motivation to understand or ‘loosen things up’, no desire to find new and more appropriate methods and no drive to share the results. If you are an analyst lacking curiosity in your role, it may be time to try a new area of focus or identify a new role.

Analysis is not one thing, it is a broad spectrum of activities. Those of us who carry out these activities have a critically important role in effective problem solving, enabling informed decision making and creating new knowledge. Analysts are not one type of person, rather varied communities of professionals with a wide range of skills and expertise.

1 Source: ITjobswatch.co.uk