The time and cost imperative underpins all project activities. Understanding the interrelationship of the measurement of the risk / reward relationship is vital for project managers if they are to deliver successful projects to time and budget.

Important topics to consider include:

- Examining the various approaches to estimating and costing inputs / outputs.

- Analysing data and budget information.

- Uses and limitations of traditional project costing and evaluation methods.

- Determining cost estimates for work packages.

- Determining what cost data to collect.

- Forecasting project schedule cost for completion.

- Defining and controlling financial tolerances.

- Defining and prioritising project resources (labour, materials etc).

Estimating and budget information

All projects carry inherent cost and financial risk and these risks have to be managed preferably from the inception of the business case (that underpins the project).

For many project managers managing budgets along the critical path becomes both a challenge and a source of frustration. For example, many business cases are premised on cost estimates of work to be done and are rarely corrected for accuracy (although project management methodologies such as PRINCE2 advocate stage (or phase) assessments.

Awareness is crucial; historically, research points out we are notoriously bad at estimating. If you estimate a task will take 10 days.

Identify how confident you are that you can deliver in 10 days by using percentages. For example, I'm only 50% certain I can deliver in 10 days. In practice you should aim for 80%. If you do not achieve 80% then re-calculate or seek advice.

In software development projects labour costs can be as much as 70 per cent of the total budget costs so errors in estimating labour costs have a compound effect and are often a major causal factor in failed projects.

Producing good estimates is very reliant on domain knowledge and processes that are proven to be repeatable and well managed. A good estimate consists of a description of the projects scope - work breakdown structure, (WBS) - the estimation technique used and the accuracy of the estimate.

The project size, cost and schedule estimation process should be premised on the requirements - traditional size estimates in software engineering projects come from using function point methods or equivalent source lines of codes.

Associated effort is usually calculated in person-hours which can be translated into cost by using applicable labour rates.

Effort, cost and schedule are all interrelated and a change in one will affect the other two. In my experience a compressed schedule usually results in a higher effort and costs.

Although I personally favour a tool such as MS Project, effort, cost and schedule can be calculated manually although this is not recommended for WBS that goes beyond two levels.

Although project tools are useful they are only tools and need to be managed like all other resources.

As a basis for budgeting and resource allocation the WBS helps by defining work packages - it could be argued that the primary function of the WBS is that of an accounting tool for summing up the task related costs for all project activities.

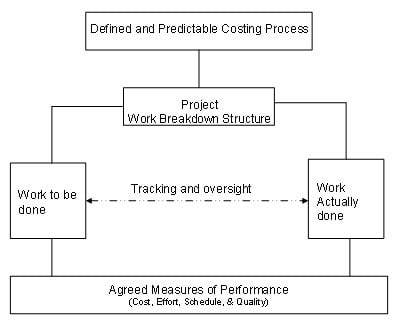

When dealing with project sponsors the WBS takes on significance in that it helps the individual understand how the project is structured and how the money is apportioned to the activities (see Figure 1).

Research shows that less than 10 percent of all projects are delivered to their original cost and schedule estimates. One reason associated with this failure rate lies in the tracking of effort and cost - estimates should be tracked over time comparing planned to actual outcomes.

The key here is to have a consistent means by which to do it and a mechanism for analysing and storing the data. Pitfalls to avoid when converting estimates to cost include:

- Unrealistic assumptions and omissions;

- Reliance on data which is historic and outdated;

- Preliminary estimates adopted without revision;

- Failure to use forward pricing rates;

- Misinterpretation of requirements (not seeking clarification);

- Lack of oversight and tracking;

- Poor judgement and knowledge.

Figure 1 Measuring and tracking resource allocation

Attributes of project cost systems

Whilst the use of propriety project management tools can help alleviate some of the mundane administration of managing project costs, the bottom line issue is what costing method to adopt and why.

In my experience setting up costing and financial systems can be a complex activity. The ploy is to keep it simple. Most seasoned project managers will testify to this key principle.

As the project manager you (and possibly your team) will need to identify the full economic costs of each project activity before they apply, and account for these costs, and ensure that such costs can accommodate within your overall budget.

The core processes that support the majority of costing methods (and systems) are direct and indirect cost accrual and variance reporting. The most important principles associated with these processes are:

- Applicability;

- Costs are fair and reasonably stated;

- Flexibility and choice of methods;

- Consistency of costing treatment;

- A system that can be audited.

Although some organisations use in-house accounting methods and standard costing a common choice amongst many project based organisations is the generic method of activity based costing (ABC).

ABC was originally designed as way to improve the allocation of overhead costs in manufacturing settings in order to develop more accurate product costs.

With this approach, overhead and indirect costs are allocated to products based on the degree to which those products actually consume the repetitive production activities of the organisation, rather than being based on a single factor, such as the number of direct labour hours associated with the product.

In more recent times ABC method as found favour with many software firms. In essence, it traces costs to specific activities undertaken by the project, such as preparing a logical design or undertaking systems testing.

The costs of these activities are then attributed to products within the WBS using estimates of usage of these activities by the cost objects (for example testing software components).

Unlike other costing methods, by inserting activities into the costing process, ABC provides the project manager (and the management team) with rich information because it gives a greater level of detail about how and why costs are incurred.

This information can lead directly to specific adjustments or modifications in a projects activity and can be used as a mechanism to streamline costs. The steps in ABC include to:

- Gain acceptance to the method.

- Plan for the costing exercise.

- Identify the WBS and products for costing.

- Ascertain core processes and activities in consultation with the project team or key staff (some testing and revision may be required to encompass all activities).

- Conduct staff effort and time estimates for each activity (the longer the timeframe over which staff time estimates are collected, the more comprehensive the required data).

- Calculate costs per activity.

- Assign cost drivers (the determinants of activity volume) and determine unit activity costs.

- Assign activity costs to WBS products.

- Undertake periodic reviews.

- Make adjustments when needed.

However it must be pointed out, ABC does not apply to every situation or project. For ABC to apply well, three conditions need to be met. They are:

- Indirect and overhead costs must be significant, and must be poorly accounted for by traditional means.

- Costing objects must exist for which management wishes to know true costs (products, customers, projects, etc.).

- Repetitive activities must exist that can serve as the basis for mapping indirect and overhead costs to cost objects.

The first two criteria go to the relative pay-off from ABC that is the pay-off will be highest to the extent that these two criteria hold. The third criterion is self-evident, in that the whole point of ABC is to use repetitive activities to better account for the costs associated with cost objects.

Value of work done (earned value)

Taken in isolation, neither the budget nor actual costs are sufficient to show the financial status of a project. What is required is a way of comparing (and combining) the project cost information to the value of work done (VWD).

One method of evaluating the VWD is to use the accounting technique of earned value (EV). EV is particularly useful in monitoring effort on large projects. The EV technique aims to answer questions in relation to the projects business case:

- Where are we today?

- Where will the project end up?

EV can be decomposed to form a cost breakdown structure (CBS) which can be combined with the WBS.

As the project progresses the actual VWD can be plotted alongside the estimates or forecast values (or the cost of work scheduled). In EV terms progress is measured as the budgeted VWD up to a specific calendar date.

One advantage of using EV is in decision making. It is easier to make small rather than large changes to the project plan. Therefore, variances from the baseline must be identified quickly - EV helps us recognise such variances and take corrective action (Figure 2).

In calculating earned value, tasks can be considered as either:

- 100 percent complete, in which case the VWD will be equal to the BCWS for the task.

- Not started, in which case the VWD will be equal to zero and the schedule variance for the task will be equal to the cost work scheduled minus VWD.

- Somewhere between 100 percent complete and not started, in which case VWD will have to be calculated based on some determination of the amount of work completed for the task.

Proper management use depends on effective and tailored analysis that is responsive to management needs. Key attributes of effective EV analysis are:

- Management support that is consistent and visible to the entire team. This reinforces the importance of EV to the project team.

- Multi-functional team approach to analysis.

- Integration of analysis of key programmatic data from a variety of sources.

- Timeliness of analysis.

- Focus on significant variances and developing trends.

- Focus on understanding the past in order to project final cost and schedule estimates.

- Management emphasis on developing credible corrective action plans.

Financial reporting and reviews

Throughout the project lifecycle senior management will need to set aside regular time periods to review budget and financial information.

Management must be prepared to contribute this time. In my experience this time is never fully factored into the project budget and for complex projects this could represent hundreds of hours. In essence the cost of this time must be budgeted and accounted for within the project.

This is necessary for three reasons:

- To reflect the true direct and indirect project costs.

- To ensure individual management commitment.

- To track contribution made by management and other project staff.

Without a formal review process, it is easy for projects to go adrift (and for costs to escalate without sanctions). Original project objectives are turned into a moving target - the project is challenged and may never achieve its original business case.

The financial review process will mitigate the risk of the project overspending and ensure that the project is kept focused and on target. Such financial and budgetary information may include:

- Monthly reporting that includes:

- time allocation (direct and indirect);

- value of work done;

- value of rework;

- lost hours (or non productive work);extraordinary purchases.

- Establishing the cost rates.

- Building up project costs that includes:

- estimating staff time;

- applying indirect costs.

- Recording and validating both direct and indirect costs.

At the end of the project, the project manager has an obligation to ensure that all costs are correctly accrued and accounted for in accordance with the procedures of the firm. This includes ensuring that a financial balance sheet is produced for audit and signature.

Documentation should be made available to audit personnel and should include a complete oversight of any adjustments or changes that have been agreed during the projects lifecycle.

Baseline and WBS management reporting taxonomy

Baseline

Frequency

Monthly, quarterly, or semi-annually.

Monthly recommended for development or high risk projects

Description

Budgeted time-phased baseline costs to end of program. This format shows significant baseline changes authorised during the reporting period. Data includes estimate at completion, contract budget base, total allocated baseline and completion dates.

Use and format

Used to determine if Over Target Baseline or Over Target Schedule has been incorporated into the programme. Data can be plotted to determine trends or if there has been a shift in the baseline. Analysis can focus on the distribution of cost for authorised changes to the baseline during the period.

Work breakdown structure

Frequency

Monthly or weekly basis as provided in business case

Description

Report WBS element performance data (for the current reporting month as well as cumulative to date data. Cost and schedule variance are calculated and reported. Identifies any reprogramming adjustment, budget at completion, estimate

Use and format

Isolate key cost and schedule variances, quantify the impact, analyse and project future performance. Performance issues isolated at lowest level and analysed for impact to overall cost and schedule variances

This article was written in June 2006 by John McManus. He is Rushmore Professor in Management Sciences and Senior Research Fellow at the University of Lincoln. Dr McManus is a specialist in systems integration and project risk management.