Since the late 20th century, the quality of interaction between humans and digital technologies has moved towards the centre stage of software development, as software has become increasingly complex and ubiquitous and users’ expectations have become more demanding. As a human-centred discipline, it is primarily concerned with users’ needs, values and behaviours, as well as goals and outcomes. Additionally, human performance and ergonomics are key considerations in safety-critical domains, where the term ‘human factors’ is often used instead of ‘UX’.

Design activities range from large scale system design to individual interface components. Everything from a washing machine to an air traffic control system requires investment in UX. Whilst successful design of digital products now has the power to support the overall success of organisations in all sectors of the modern economy, failure has the potential to cause real frustration, inconvenience and possibly danger in people’s lives.

What knowledge do we need?

Increasingly, people want to feel they are in control and empowered by digital technology and are vocal about their experiences. There is more general awareness of usability issues than ever before and terms such as ‘user-friendly’ have become part of our everyday vocabulary. Even where technical vocabulary is not used, understanding of what makes successful design is often apparent. For example, public reviews of mobile apps often indirectly refer to attributes such as learnability and speed of use. Everyone can be involved in UX.

But, optimising the user experience requires much more. In particular, all UX design should be informed by UX research. Generally, in-depth information on users’ goals, values, context of use and other factors such as demographics should be obtained before any design takes place. It should be built into the iterative development cycle, with regular UX evaluations taking place to ensure designs are progressing in the right direction and meeting business objectives.

A skilled researcher is able to provide rich, reliable and actionable data that avoids bias. Whilst basic usability testing techniques are fairly well-known, advanced interdisciplinary knowledge across cognitive science and humanities enables researchers to deploy advanced techniques in research design, execution and analysis, triangulate findings and develop tailor-made methodologies which capture even the hidden facets of users’ real experience.

Likewise, an academic grounding in UX design enables designers to interpret and apply UX research effectively, utilise established theory in design work and tap into more advanced design practices such as participatory design.

Another benefit of formal training in UX is the development of thinking skills. This is particularly important as UX practices portray a curious mix of design thinking, engineering approaches and scientific enquiry, which feed into the robust analysis of problems and solutions. These skills are highly transferrable, but UX education also has ethical purposes: it nurtures empathy and compassion for others.

Current challenges

Despite this, UX education remains patchy. The UK school computing curriculum has encouraged students to develop their own software, particularly since its substantial revision in 2014. But, although the needs of the user are considered in computing lessons, the term ‘user experience’ is unlikely to be used and the development of UX knowledge is relatively unstructured.

Similarly, there is very little provision of specialised UX education in universities. Only seven undergraduate and 18 postgraduate programmes are available in the UK for the 2021 intake. Most computer science degree syllabi have a ‘token’ UX module and psychology and sociology degrees often incorporate relevant topics such as user behaviour on social media, but this is insufficient for specialisation.

In fact, it can be quite difficult to transfer to UX from other fields such as computing, psychology or graphic design, as there will be crucial elements of knowledge missing. Of course, conferences, boot camps, workshops, short courses and on-the-job training in UX are available, but the learner needs to make quite challenging links from one domain to another and will start with a lop-sided view of UX.

More advanced, accredited educational opportunities at school and university level would enable learners to demonstrate competence and immediately apply the level of knowledge that would be expected in many other fields. As it stands, there is heavy reliance on candidates’ experience and portfolios when recruiting for UX positions.

Setting standards

In order to achieve more accessible, streamlined career paths and better UX education generally, a useful starting point is professional standards. A good example is the Skills Framework for the Information Age (SFIA Foundation), which specifies four UX skill areas: user research, UX analysis, UX design and UX evaluation. The progression of different ‘levels’ of expertise, up to level six, is explained within each area.

This can be used by educators as a point of reference and as a tool by UX specialists to assess and improve their knowledge. It can also be used to help illustrate competency as part of applying for Chartered IT Professional status, which helps to endorse the professional standing of UX alongside other specialisms.

Putting it into practice

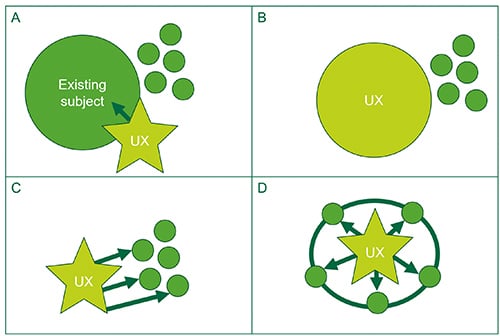

There are various ways in which UX education can be strengthened in the future (Figure 1), which could potentially apply at various phases of education. Firstly, UX could be given a stronger identity within an existing subject area such a computing or psychology (A). This subject would have ‘ownership’ of UX. This would work particularly well at school level where it may be impractical to teach UX separately, although upskilling of teachers and adjustments to the syllabus would be necessary.

Secondly, it can be taught as a standalone subject (B). This requires the most dedicated time, but at school level could materialise as a series of special workshops or an after school club.

It is unfortunate that UX at universities continues to be overlooked, although this may be because it is a relatively new subject and because it does not sit naturally within any one traditional university department (currently UX courses may be run within design, psychology or computing departments).

Thirdly, UX may be integrated into existing subjects as a recurring topic (C). This would work well at school level, provided subject terms were used consistently and students were able to make the links when applying their knowledge of UX in different subject areas.

Similarly, UX could be considered a cross-curricular theme (D), with no responsibility for its delivery attributed to any particular curriculum area. This may work well in primary school education with topic-based learning and could apply wherever pupils present their work as a digital product or artefact with a specific audience in mind.

Action

Whilst each of these implementation strategies have merit in different contexts, the current priority for learners is creating a joined-up learning journey with accessible entry points.

Current educational provision is not robust enough to support the challenges of 21st century interface design and unless action is taken, this gap will only widen with ever more complex technology and high user expectations.

UX creates a better digital world for us all, so it is worth the investment - for society, individuals and the economy.