When art met computers whole new movements and possibilities in creativity were enabled. Artists explored new worlds of sound and built images that would be otherwise impossible to create. Movie makers were presented with new techniques and even tapestry, as a form of expression, was transformed by technology.

Much of this adventure has been chronicled in BCS’s Computer Bulletin and later in ITNOW. For decades, John Lansdown wrote a column called Not only computing - also art. It detailed the meeting of art and computers and reported on defining new ideas.

The BCS Computer Art Specialist Group - formed by Alan Sutcliffe, George Mallen, and John Lansdown in 1968 - was created to inspire the use of computers by artists. It encouraged creatives to share information and knowledge about music, performance art and visual creativity.

Here are 12 works and pieces that capture the spirit of computer art’s evolution.

1. Digital tapestry

This image by Turner Prize-winning Grayson Perry shows that he has more strings to his bow than pot-making. ‘Hold Your Beliefs Lightly’ is a computerised textile work (really a small flag) inspired by African Asafo flags in the British Museum’s collection and featured in Perry’s exhibition ‘The Tomb of the Unknown Craftsman’. Programmed by Tony Taylor, the work was 32.5x45cm. (image copyright the artist)

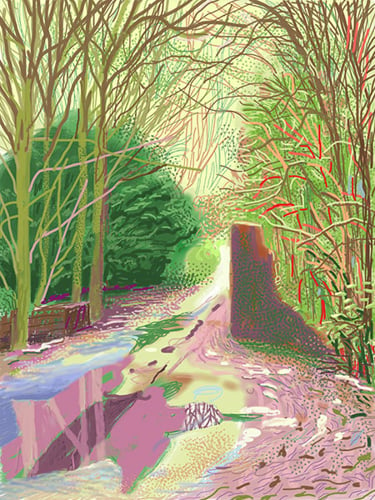

2. Hockney's iPad in Yorkshire

In 2011 David Hockney turned his attention to the iPad and created a group called the ‘Arrival of Spring in East Yorkshire’. It was made on the iPad, was printed out on a large scale and was shown at the Royal Academy.

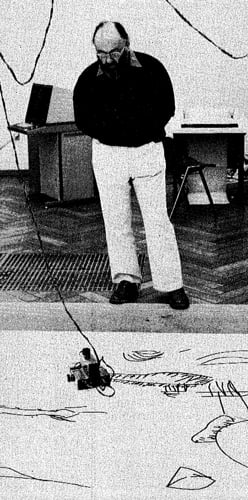

3. The drawing turtle

In March 1978, John Lansdown detailed a trip to Amsterdam. There he encountered Harold Cohen’s latest work. The work consisted of a device for making drawings under computer control. The little robot turtle could draw freely on floor areas of about 200 square feet. The images were childlike and were produced by the program following a set of 300 rules. The program was event driven and the turtle had basic sensors which influenced the outputs.

4. Making art from DTP

Back in 1988, graphic designers began breaking the familiar two column grid and experimenting with type. Using a laser printer and a Macintosh, student designers experimented with innovative shapes, curves and paths for text layout.

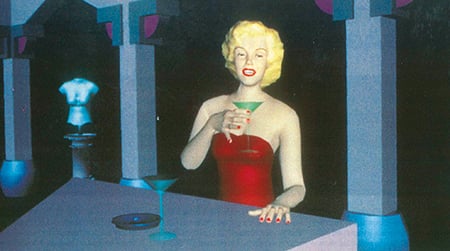

5. Synthetic actors

Acting as a form of art and expression looked like it was under fire from computers in 1989. ITNOW reported on how researchers were looking to build synthetic actors - digital thespians who, thanks to increases in processing and graphics power - began to look like their real counterparts. As the research advanced, it was put to the test and movie shorts were produced. Among them was ‘Rendez-vous in Montreal’. It tells the story of a meeting between Humphry Bogart and Marilyn Monroe. Death was undone and kisses were exchanged.

6. Hundreds of years before the dawn of history

Ms Semmannia Luk Cheung - a student at Middlesex Polytechnic - won a commendation in the Baillie Gifford Technology Fund Competition, organised by the Computer Arts Society. Ms Cheung’s image showed a robot at Stonehenge and it took pride of place on the front cover of September 1986’s Computer Bulletin.

7. The film Pixillation

In the early seventies, artists began using computers to automate their work. Machines could, it was realised, generate large amounts of material from which the artist could select elements and examples. Lillian Schwartz’s ‘Pixillation’ from 1970 was a four minute video consisting of computer-produced images and Moog-synthesised sound. It was made using an XPLOR system at Bell Laboratories.

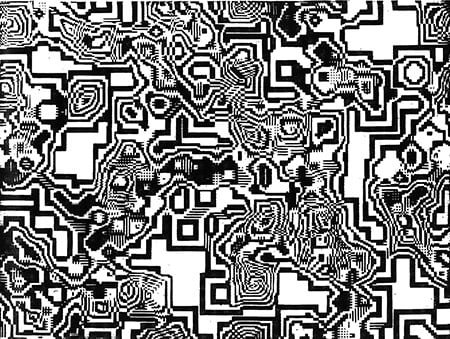

8. The anatomy of a bug

In the early 1980s, BCS Computing At Schools member, Jonathan Yonge, used his Calcomp system (a vintage plotter) to draw shell-like spirals. The images were undeniably beautiful and one was used on the front cover of Computer Bulletin in June 1984. Yonge also published the images where his computations went wrong. These were similarly mesmerising, looking like alien architecture.

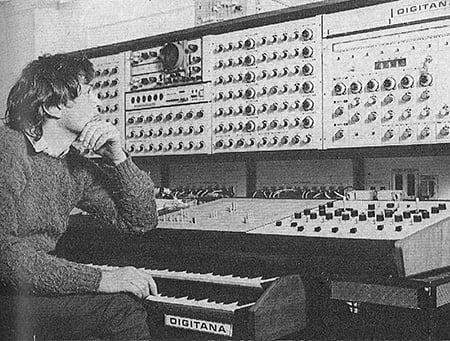

9. Synthesised music

The use of computers in music received further impetus with the production of the SYNTHI 100. The high voltage controlled electronic music synthesiser was produce by EMS of London. At the SYNYHI 100’s heart was a computer that could store 10,240 bits. It acted as a sequencer capable of controlling six different parameters - such as pitch or amplitude.

One of the most notable performances by a SYNTHI 100 was the incidental music for the 1972 Doctor Who series, The Sea Devils. In the BBC’s hands, the synthesiser also appeared in Blake’s 7 and the radio version of the Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy.

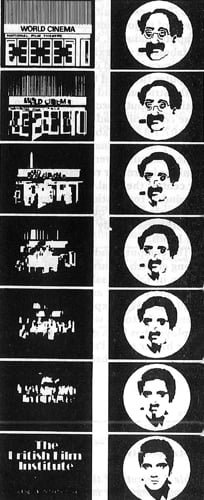

10. Uncontrolled transformation

Two filmmakers called Alan Kitching and Colin Emmett devised a system called Antics to help them make animated films. The cells above show Groucho Marx morphing into Elvis Presley and a cinema frontage becoming title text. The former was an example of uncontrolled transformation while the latter was described as controlled. The process involved an ICL 1906A computer, a DMAC digitiser and a plotter.

11. Rendering becomes more real

In June 1988, John Lansdown reported on developments being made in rendering. Rather than just producing representations of regular and angular objects, Lansdown explained that artists had begun to tackle intricate and irregular shapes - like the human face. The modelling techniques being developed mapped virtual muscles onto digital skeletons so allowing creatives to build believable facial expressions.

12. Making digital stars

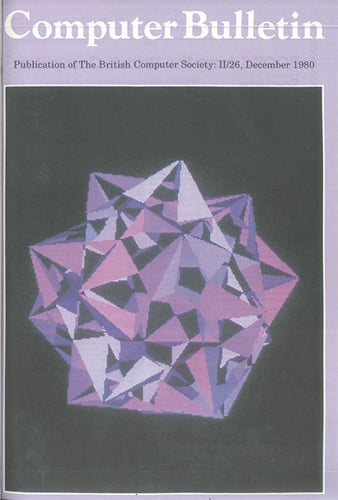

This image feels like it captures a moment in the evolution of computer art’s development. The work stems from a paper called ‘Creating Polyhedral Stellations’, written by Professor Badler and Kathleen McKeown. Far from a new idea, the intensely mathematical stellations were actually first discovered in the 17th century.

Computers, however, enabled the explorations of complex shapes and for new geometric bodies to be created. These included shapes with exotic names like the Rhombicosidodecahedron and the Triakis tetrahedron.