On 18 September 2013 the Financial Times summed up the situation as follows: ‘There are several ways the US Air Force could have wasted $1.1bn. It could have poured tomato ketchup into 250m gallons of jet fuel or bought a sizeable stake in Bear Stearns. Instead it upgraded its IT systems.’

Over the last few decades, those of us working in the information systems industry have tried various approaches and means to improve the chance of delivering successful IS projects.

These have ranged from adopting formal analysis and design methods to increasing the level of collaboration with customers. Studies looking at the causes of problems often focus on issues related to governance, lack of user involvement and poor requirements.

While governance is concerned with what Drucker called ‘doing things right’, ensuring that we are ‘doing the right things’ is also extremely important. Requirements are not poor per se, but they are often subjected to limited analysis or are documented poorly.

Equally, they may not be elicited with care, not relate to the business needs or fail to address the issue to be resolved. However, in some situations, it is not possible to address the real issues because there has not been any attempt to determine what these issues actually are. Answering the question: ‘what problem are we trying to address here?’ is critical for a successful IS project, but somehow all too often this is missed.

Requirements are defined in order to ensure that the business operates efficiently. They are related to business objectives and critical success factors (CSFs). They are a response to a recognised and understood ‘root cause’ of a problem.

And, to really understand why requirements are not correct or are poorly described, we need to adopt a business analysis approach, investigating the root causes of poor requirements so that we can overcome them and ensure business requirements are understood before we leap into adopting a ‘solution’.

Too often, change programmes are initiated because someone (typically at an executive level) has a ‘great idea’. Perhaps they have had a discussion about a new software package with an acquaintance who works for a competitor or partner organisation, or they have heard about a terrific new technological development, or have picked up a book extolling the virtues of a new business model.

But this does not mean that the idea will work in every organisation and, even more critically, it focuses on the solution before understanding the problem to be resolved. If we do not understand the problem to be addressed or the opportunity to be grasped, we have a fatal flaw in the proposition.

In other words, if the justification for the project is solely that someone else has tried it, then it is almost certain to fail. Similarly, if an idea is not evaluated for its potential impact, then the opportunity exists for highly disruptive - perhaps destructive - results. At best, the resultant change programme will be ‘challenging’, at worst, we will be looking at failure.

In our private lives, would we embark on a significant purchase without (a) understanding why and (b) thinking through the outcomes we would want? I would hope most of us would answer with a resounding ‘no’. And yet we hear of projects that are set up with the vaguest of intentions.

I once asked a business manager what he would like to achieve through a proposed project. His answer was ‘increased profit’ and no amount of further discussion could gain any clarification. He had seen a competitor use a similar solution so wanted it in his company irrespective of how it would meet any business objectives, help achieve defined CSFs or impact the existing people, processes and systems.

Business analysis is utilised differently in different organisations. Many organisations have recognised the value that business analysts bring and have engaged in the ongoing development of the BA practice, thus ensuring that projects address real needs. However, some organisations do not appreciate the value of business analysis and even if a BA practice exists, it is a ‘hidden gem’, offering significant capability that is under-utilised.

As a specialist discipline, business analysis ensures that organisations don’t jump to hasty solutions and don’t waste the vast amounts of funds spent on the all-too-often publicised project failures.

The key factor here, though, is the word ‘specialist’. Business analysis is conducted by professionals with a toolkit of techniques and competence in a range of skills. They understand the business domain and the stakeholders with whom they are concerned to engage and communicate, and to whom they provide support.

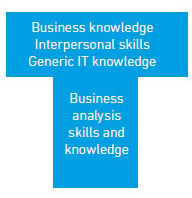

But these skills are held by many IS professionals so what makes business analysts the right people to investigate ideas and problems, and identify and help evaluate the potential solutions? The answer may be seen in the ‘T-shaped professional’ model for business analysts shown in figure 1.

Figure 1. T-shaped BA professional

The horizontal bar in figure 1 shows the generic business and IT skills required of IS professionals and the vertical bar sets out the ‘deep’ areas of specialist BA competence, which here relate to key business analysis skills such as problem investigation, situation analysis, requirements engineering and solution evaluation.

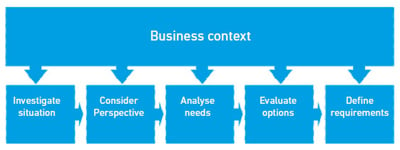

Specialist business analysts require this skill set in order to be able to conduct the range of activities included in business analysis work. These activities are shown in the BA process model in figure 2, which sets out clearly the responsibilities of a business analyst and the strategic context within which they are constrained and performed.

So, if business analysts are ‘T-shaped professionals’, with the skills and knowledge required to conduct the activities shown in the BA process model, why is it that, if the analytical work is conducted, it is often undertaken by other professionals (with similarly extensive skills, but in different ‘deep’ areas)?

This is a recipe for hasty judgements on solutions, a failure to consider tacit knowledge, a tendency to accept assumptions and a lack of focus on root causes. And, if a change project begins with this inadequate level of analysis, it is not too hyperbolic to say it is doomed.

Figure 2: Business Analysis Process Model

Ultimately, we all want the same thing - to ensure our organisations work effectively by deploying the best systems and processes to support the work performed by skilled people. To achieve this, we have to think before acting, which means we investigate and analyse before committing funds to unwise investments. Business analysis is a hidden gem in too many organisations. It is time to raise its profile so that IS projects have a better chance of delivering business success.