Who in the enterprise architecture (EA) community has not heard that EA efforts should start from business strategy? Asks Svyatoslav Kotusev, Enterprise Architecture researcher.

The idea of the primacy of strategy in EA initiatives is likely to be familiar to virtually everyone as it is loudly voiced and permeates, explicitly or implicitly, through much of the EA discourse. For many people, it is almost axiomatic that architectural planning should ensue from and enable organisational business strategy (importantly, in this article, the term ‘business strategy’ is used in a narrow sense, specifically as a highest-level mission, vision, goals and objectives of an entire organisation, while ‘architectural planning’ refers only to the strategic planning process that converts business plans into the desired portfolio of IT investments1).

The idea of commencing architectural planning right from business strategy is disseminated by numerous sources. For instance, the current so-promoted ‘industry standard’ TOGAF2 lists business goals and some other contextual information as the core input to its early phases, whereas its subsequent phases generate tens of various diagrams, catalogues and matrices with little or no (or vague and unspecified) additional input, as if a detailed target architecture for an organisation is deduced mostly from its business context and strategy.

Likewise, certain books on enterprise architecture authored by industry gurus3, 4 also create an impression that the recommended sets of EA models defining the desired target state and future course of action all naturally originate, for the most part, from environmental analysis, top-level business strategy, goals and objectives. Some of these books are even titled accordingly: ‘From Business Strategy to IT Action’5 and ‘From Business Strategy to Information Technology Roadmap’6. More aggressive gurus go to extremes and blurt point-blank: ‘No strategy, no enterprise architecture’7 (page 6), ‘No strategy, no architecture. No vision, no architecture’8 (page 11).

Or take, for example, Gartner. The authors of its EA process promoted during the period of hype around enterprise architecture claimed that ‘future-state EA is directly derived from business strategy’9 (page 5) and argued that ‘the goal [of the EA effort] is to translate business strategy into a set of prescriptive guidance to be used by the organisation... in projects that implement change’9 (page 8). Even Gartner’s former official EA definition began with asserting that ‘enterprise architecture is the process of translating business vision and strategy into effective enterprise change’10 (page 3), while their current glossary starts indistinctly but adds that ‘EA delivers value by presenting business and IT leaders with signature-ready recommendations for adjusting policies and projects to achieve targeted business outcomes’.

Undoubtedly, Gartner’s promise to provide ‘signature-ready’ transformation plans ‘directly derived from business strategy’ rings sweet and alluring to executive ears, and also lucrative to Gartner itself and other consultancies willing to extend their client bases. Surely, such claims sound very cool if you wish to sell your EA consulting services to top managers, but are they realistic? Do these statements accurately reflect how EA practices actually work in organisations? Do they represent a reasonably precise description of what real enterprise architects tend to do? Or, do they set a proven standard of perfection that all EA practitioners should strive to achieve?

Problems with business strategy

Interestingly, many attempts to develop actionable plans out of business strategy to enable it are precluded, first of all, by the symbolic and elusive nature of strategy itself. For example, a rather common industry situation with business strategy can be vividly illustrated by the following jocular quote of Jeanne Ross, a former principal research scientist at MIT Sloan Center for Information Systems Research (CISR): ‘I remember IBM saying, “Our strategy is, we’re gonna raise share price to $11 per share”, and I thought, “Who the heck is gonna enable that strategy?”’.

In fact, decades of research on information systems planning have long identified a broad spectrum of problems associated with business strategy as a basis for acting11. Strategy can be vague, ambiguous and interpreted differently by different people (e.g. ‘become number one’ or ‘provide best services’). Strategy can be purely aspirational and consist of mere motivational slogans (e.g. ‘get closer to the customer’ or ‘leverage synergies’). Strategy can comprise various objectives and indicators offering no actionable hints, especially for IT (e.g. ‘increase market share by X%’ or ‘grow revenue to $Y’). Strategy can be market sensitive, deliberately obscure and surrounded by secrecy (e.g. partnerships, mergers and acquisitions). Strategy can be unstable, volatile and can change its direction dramatically several times a year (e.g. management turnover, political churn or sales-data-driven decisions in retail). Strategy can concentrate on the business aspects that are changing, but neglect some of the more fundamental pillars that remain the same (e.g. new capabilities instead of core ones). Finally, formal business strategy can be simply missing altogether (e.g. privately held companies).

The prevalence of these problems across the industry should not be understated as they are not at all exceptions or deviations from the norm. On the contrary, they are far more typical than not. Ironically, the surveys of Gartner, the very same company that intended to derive target architecture directly from business strategy, tell us that ‘two-thirds of business leaders are unclear about what their business strategy is’12 (page 2), only ‘33% [of EA practitioners] stated that their business strategy is well-understood’13 (page 1), but ‘over 60% of what organisations have defined as ‘strategy’ is actually a set of business goals and desired outcomes’14 (page 3). So, what kind of architectural plans can you derive from business strategy?

How architectural planning really happens

During my earlier studies of EA practices in organisations, I have long noticed that business strategy, in fact, occupies a rather peripheral position in the daily conversations and activities of enterprise architects giving way to much more mundane things, like business capabilities and specific business needs15 (and I was definitely not the first one to observe that). To further explore this peculiarity, I interviewed more than 20 EA practitioners with an intention specifically to figure out how architectural plans are actually developed in their organisations in a way that aligned with their business strategies and needs. All the interviewees held the title ‘enterprise architect’ and worked in diverse Australian companies of various sizes and industry sectors. My analysis demonstrates that the situation in practice differs considerably from the one portrayed in the mainstream EA literature, where architectural plans are (somehow) derived directly from business strategy, and also reveals a number of remarkably consistent patterns of architectural planning that tend to apply to the vast majority of organisations, of course with some variations and important caveats discussed later.

Business strategy is not actionable

Firstly, all the problems with business strategy outlined earlier have been confirmed: it was usually characterised by enterprise architects as vague or inarticulate, often as fickle and in some cases it was absent. Although the interviewees generally acknowledged the importance of strategy as an overall context and some of them even distinguished certain informative signals in their strategies, all of them unanimously opined that, taken on its own, it offers no substance in terms of actionable suggestions for architectural planning.

Unsurprisingly, virtually all enterprise architects did not regard C-level executives, who formulated corporate strategy, as their stakeholders and rarely, if ever, communicated with them. Some architects pointed out that top managers are too remote from routine business operations to have any ideas of what needs to be changed in the organisation to execute strategy and engaging with them, thus, is unlikely to be valuable.

Business unit plans provide useful input

Secondly, all the interviewed architects viewed lower-level business unit plans as the primary input for architectural planning (business units can be different corporate divisions, business functions, lines of business or geographies, depending on the organisational structure). Unlike abstract and grandiose business strategy, business unit plans deal with more down-to-earth, operational issues that can be used by enterprise architects as a solid basis for thinking of possible changes in information systems. Accordingly, all the interviewees reported that their key stakeholders are typically heads of various business units, who are located one, two or sometimes three levels below the C-level in the corporate hierarchy.

Business unit plans have many drivers

Thirdly, business unit plans that provide a foundation for architectural planning are shaped by multifarious drivers. One of these drivers is local strategies that define long-term goals, objectives and courses of action for the individual business unit. Strategies of business units are normally developed by senior executives, almost always without any involvement of enterprise architects, and ensure the linkage of business unit plans to top-level strategy.

However, besides their local strategies, business unit plans are also formed by multiple additional, non-strategic factors. Albeit these factors are manifold, most of them can arguably be related to one of the following broad categories: operational problems (e.g. known issues, existing bottlenecks and pain points), ad hoc demands (e.g. customer needs, competitor moves and regulatory changes), permanent imperatives (e.g. constant objectives, fundamental capabilities and operations) and technical concerns (e.g. technology strategies, optimisation opportunities and necessary upgrades). As most forces shaping business unit plans stem from sources other than corporate strategy, they can be largely decoupled and the alignment between them tends to be rather loose and not particularly evident.

Business unit plans are converted into roadmaps

Fourthly, business unit plans get converted into IT investment roadmaps collaboratively by local business leaders and enterprise architects. The question of how exactly this conversion happens practically in different situations deserves detailed scrutiny and writing another lengthy article. Here, it would be sufficient to say that the translation of business plans into specific IT initiatives is accomplished through deep dialogue between managers and architects, typically with the help of various visions, and sometimes considerations, EA artifacts16, e.g. business capability models, high-level process maps and value chains, less often architecture principles, strategies, target states or more exotic documents17. Brief summaries of locally agreed roadmaps can be presented to C-level executives for their notification and approval.

Global optimisation occurs bottom-up

Lastly, global optimisation of architectural plans is achieved not by ‘grand’, all-encompassing top-down planning, but rather by means of seeking synergies in separate business unit plans in a bottom-up manner. Namely, enterprise architects analyse different business unit plans, compare them with each other, find overlapping needs, diagnose common problems and identify redundant systems. This information is then incorporated into the resulting roadmaps via proposing initiatives beneficial for the organisation as a whole.

Integrative model of architectural planning

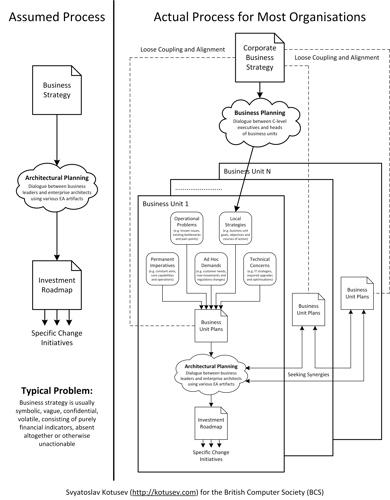

The five patterns, described above, all address different aspects of architectural planning. As these patterns are interrelated, they can be integrated into a unified conceptual model reflecting the actual process of architectural planning end to end. Schematic graphical representations of the assumed and actual processes of architectural planning are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Assumed and actual processes of architectural planning (click to view larger image)

The actual process of architectural planning depicted in the right-hand side of Figure 1 clarifies the realities of enterprise architecture related to developing IT investment roadmaps aligned with business strategies (as noted earlier, this model specifies only the strategic planning process, but does not cover initiative delivery and technology optimisation1). Most importantly, it indicates that architectural planning in practice is based on concrete business unit plans, not ethereal business strategy. This fact explains how enterprise architects cope with the vagueness, superficiality, fluidity and absence of business strategy.

Interestingly, and contrary to some people’s deep-seated beliefs, because most drivers of business unit plans are strategy-neutral, architects can potentially perform meaningful planning and add value when both corporate and business unit-level strategies are missing. Even in the worst-case scenario of deficiency of any specific business ideas, they can often resort to purely technical concerns and try to rationalise the existing IT infrastructure to reduce maintenance costs, enhance overall business flexibility and help accommodate future needs.

Caveats and limitations of the model

And finally, a few words of caution. The presented model describes the generic process of architectural planning observed in an ‘average’ organisation, irrespective of industry. Size-wise, this model seems to be relevant to a very wide range of companies, say the middle 80-90% of the distribution, but significant deviations can be expected at both the low and high ends of the spectrum.

On the one hand, in small companies (e.g. those employing only one enterprise architect), that also tend to be private ones, the planning process is likely to be simpler. For example, C-level executives can be knowledgeable in business operations and represent direct stakeholders of architectural planning, business strategy can be more material and actionable, while the separation of a company into different business units with their own plans and agendas can be less noticeable. Under these conditions, the situation can more resemble the idealistic assumed process shown in the left-hand side of Figure 1.

For you

Be part of something bigger, join BCS, The Chartered Institute for IT.

On the other hand, in very large and complex enterprises (e.g. holdings with multiple subsidiaries), the planning process will be more sophisticated. Due to an increased number of levels in the accountability structure and greater distancing of senior managers from operations, the business planning part of the model will most probably be expanded. In short, the model is valid for a typical organisation and most organisations, but it is not universal and unlikely to be accurate for the smallest and largest of them.

Also, companies can occasionally launch global transformation programmes transcending the boundaries of their business units, e.g. corporate mergers and major restructurings. Such programmes are driven straight from the top, coordinated at the chief executive level, follow unique pathways and certainly represent an exception to regular architectural planning reflected in the model.

Can enterprise architecture be based on business strategy?

The model discussed in this article resulted from the analysis of EA practices in many real-world organisations and it clearly demonstrates that, at least in the studied companies, architectural plans are not derived directly from business strategy, as it is widely advocated. Is this situation normal or abnormal, accidental or fundamental? Are there any opportunities for overcoming the difficulties associated with immediate strategy-based planning? Can enterprise architecture, after all, be based on business strategy?

The available body of knowledge on organisations suggests that the observed situation is actually quite natural and dictated by fundamental reasons. On the one hand, large companies are political entities with multiple constituencies where ambiguous strategies, due to their ability to present different (preferred) versions of reality to different parties, are necessary to lessen potential conflicts and unify all managers under the common agenda18. On the other hand, business strategies of public organisations are often oriented towards external stakeholders and created more for the purposes of public relations to impress outsiders, e.g. ‘an organisation that is failing can announce a plan to succeed’19 (page 215). Hence, in large, public organisations, which in the EA context arguably constitute the vast majority of organisations, business strategies tend to be vague and symbolic by necessity and cannot be expected to be clear and actionable. At the same time, because of the functional specialisation of employees in organisations, enterprise architects simply cannot know the needs of different business units better than their managers. In these circumstances, starting architectural planning from business unit plans formulated by their leaders provides essentially the only viable option for architects.

Therefore, the very idea of strategy-based EA efforts periodically circulating in the EA community is substantially chimeric and, for objective reasons, unsuitable for most companies. Though attractive as a practical ideal and a sales pitch, strategy-based architectural planning actually represents a rather hackneyed and meaningless cliché that has no substance, offers no actionable guidance and is basically misleading. Claiming that EA-related activities (just like everything else in organisations) should be aligned with business strategy is a riskless statement and truism, which is hard to disagree with, but even harder to put in practice. Similarly to systems thinking and agile architecture, strategy-based planning is easy to argue for, but difficult to specify precisely, let alone implement. Deriving architectural plans directly from business strategy to achieve perfect alignment, as promoted by many, thus will never turn into an organisational reality, like all other utopian dreams of management gurus and visionaries, e.g. abolishing bureaucracy, eliminating hierarchy, establishing self-organising teams and creating composable businesses. And no amount of indignation or laments that ‘it should not be like that’ is going to change the situation.

Takeaways for enterprise architecture practitioners

So, what is the moral of the story told above for pragmatic EA practitioners? Although issuing specific prescriptions is rather naive, if not dangerous, some general pieces of advice can arguably be given:

- Study and appreciate your business strategy, but do not expect to produce any actionable plans out of it

- Identify relevant decision-makers who understand how the business is operating and how it can be improved, those are likely to be heads of business units and their deputies

- Ask these stakeholders what their needs are, discuss what IT can do to address them and prioritise the respective initiatives in roadmaps to shape the investment portfolio

- Link the proposed initiatives back to strategic goals, as if they come straight out of business strategy, to justify their necessity for the organisation

All in all, enterprise architects should realise the difference and conceptual decoupling between widely publicised but largely nominal business strategy and inconspicuous but actionable business unit plans. Accordingly, they should not get fooled or distracted by the ‘wonderful’ idea of strategy-based planning, but rather seek more tangible input for their planning efforts.

About the author

Svyatoslav Kotusev is an independent researcher, educator and consultant. Since 2013 he has focused on studying enterprise architecture practices in organisations. He is an author of the book ‘The Practice of Enterprise Architecture: A Modern Approach to Business and IT Alignment’ (now in its second edition), many articles and other materials on enterprise architecture that have appeared in various academic journals and conferences, industry magazines and online outlets. Svyatoslav received his PhD in information systems from RMIT University, Melbourne, Australia. Prior to his research career, he held various software development and architecture positions in the industry.

References

1 EAP on a Page (2021) ‘Enterprise Architecture Practice on a Page (v1.1)’, http://eaonapage.com: SK Publishing.

2 Kotusev, S. (2018) ‘TOGAF: Just the Next Fad That Turned into a New Religion’, In: Smith, K. L. (ed.) TOGAF Is Not an EA Framework: The Inconvenient Pragmatic Truth, Great Notley, UK: Pragmatic EA Ltd, pp. 27-40.

3 Holcman, S. B. (2013) Reaching the Pinnacle: A Methodology of Business Understanding, Technology Planning, and Change, Pinckney, MI: Pinnacle Business Group Inc.

4 Bernard, S. A. (2020) An Introduction to Holistic Enterprise Architecture (4th Edition), Bloomington, IN: AuthorHouse.

5 Benson, R. J., Bugnitz, T. L. and Walton, W. B. (2004) From Business Strategy to IT Action: Right Decisions for a Better Bottom Line, Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

6 Pham, T., Pham, D. K. and Pham, A. (2013) From Business Strategy to Information Technology Roadmap: A Practical Guide for Executives and Board Members, Boca Raton, FL: Productivity Press.

7 Schekkerman, J. (2006) ‘Extended Enterprise Architecture Framework Essentials Guide, Version 1.5’, Amersfoort, The Netherlands: Institute for Enterprise Architecture Developments (IFEAD).

8 van't Wout, J., Waage, M., Hartman, H., Stahlecker, M. and Hofman, A. (2010) The Integrated Architecture Framework Explained: Why, What, How, Berlin: Springer.

9 Bittler, R. S. and Kreizman, G. (2005) ‘Gartner Enterprise Architecture Process: Evolution 2005’ (#G00130849), Stamford, CT: Gartner.

10 Lapkin, A. (2006) ‘Gartner Defines the Term 'Enterprise Architecture'’ (#G00141795), Stamford, CT: Gartner.

11 Kotusev, S., Kurnia, S., Dilnutt, R. and Taylor, P. (2020) ‘Can Enterprise Architecture Be Based on the Business Strategy?’, In: Bui, T. X. (ed.) Proceedings of the 53rd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Maui, HI: University of Hawaii at Manoa, pp. 5613-5622.

12 Cantara, M., Burton, B. and Scheibenreif, D. (2016) ‘Eight Best Practices for Creating High-Impact Business Capability Models’ (#G00314568), Stamford, CT: Gartner.

13 Burton, B. and Allega, P. (2011) ‘Enterprise Architects: Know Thy Business Strategy’ (#G00210256), Stamford, CT: Gartner.

14 Burton, B. and Bradley, A. J. (2014) ‘Deducing Business Strategy Is a Unique Opportunity for EA Practitioners to Both Drive Execution and Gain Credibility’ (#G00262166), Stamford, CT: Gartner.

15 Kotusev, S. (2021) The Practice of Enterprise Architecture: A Modern Approach to Business and IT Alignment (2nd Edition), Melbourne, Australia: SK Publishing.

16 Kotusev, S. (2019) ‘Yet Another Taxonomy for Enterprise Architecture Artifacts’, Journal of Enterprise Architecture, Vol. 15, No. 1, pp. 1-5.

17 EA on a Page (2021) ‘Enterprise Architecture on a Page (v1.4)’, http://eaonapage.com: SK Publishing.

18 Pfeffer, J. (1981) Power in Organizations, Cambridge, MA: Ballinger Publishing Company.

19 Mintzberg, H. (1994) The Rise and Fall of Strategic Planning: Reconceiving the Roles for Planning, Plans, Planners, New York, NY: The Free Press.