IEEE milestone plaques celebrating the Manchester Baby and Atlas computer’s uniquely foundational place in the pantheon of electrical science’s greatest inventions, were unveiled during a recent event in Manchester.

The Small Scale Experimental Computer and a computer called Atlas are two machines that changed the world. Their contribution to computing as we know it today, their makers’ revolutionary thinking and their city of birth, were all celebrated by unveiling two commemorative plaques.

The Small Scale Experimental Computer was begun in 1946 by two of computing’s true pioneers: F.C. (Freddie) Williams and Tom Kilburn.

Nicknamed the Baby, the computer contained the first cost-effective random access memory. When tested at 11am on 21 June 1948, the Baby demonstrated, for the first time, a stored programme running on a general-purpose computer – a design principle which lives and breathes in all of today’s computers, whatever their shape and job of work.

The Atlas computer was, for a brief moment in time, believed to be the most powerful computer in the world. According to the Computer Conservation Society, ‘it was said that when Atlas goes down, the computing capacity of the entire country is halved.’

However, it wasn’t the machine’s power for which it received the IEEE Milestone Award. Rather, it was the machine’s use of virtual memory. This revolutionary approach allowed memory of different types, speeds and capacities to act together as a single, large and fast memory, which could be made available to multiple users. This approach, like Baby’s ability to run stored programmes, is a cornerstone of how modern computers still work today.

Fittingly, both plaques were unveiled at an event held at Manchester University’s Kilburn building on 21 June 2022 (the 74th anniversary of Baby’s first test).

The historical significance of the Manchester Baby

Despite its achievements, the original Manchester Baby – built as it was from a rag-tag collection of scavenged, redundant and spare parts – was eventually scrapped.

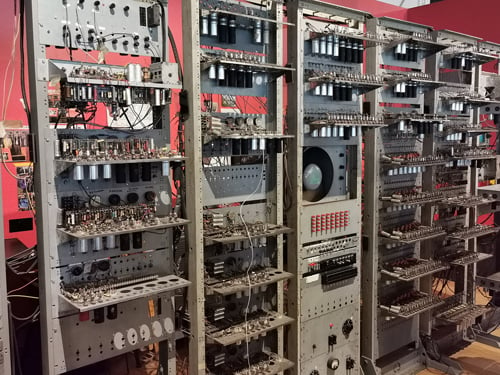

To mark the Baby’s 50th anniversary in 1998, a team of Computer Conservation Society (CSS) members and other volunteer experts (headed by Chris Burton from the CCS) set about building a replica Manchester Baby.

Fully working and fastidious in its detailing – down to daubed text, blinking lights and a functionally important cardboard box (look closely at the Baby’s photograph, under the circular cathode-ray tube) – the replica now lives at Manchester’s Science Museum.

‘It’s a triumph that we’re standing here today,’ said Burton.

For you

Be part of something bigger, join BCS, The Chartered Institute for IT.

Addressing the Baby’s historical significance, he explained: ‘The pioneers, the people who built the original, only had a partial idea about its significance. They saw it as some kind of giant slide rule: calculators didn’t exist at that time. It was a tool for engineers and scientists to progress their research. The vision of a commercial computer just wasn’t on the horizon.’

The Baby did, however, herald the age of commercial computing – and it did so very quickly. The machine was soon enlarged, upgraded and dubbed The Manchester Mark I. Again quickly, the local computer firm Ferranti Ltd produced a re-engineered production version of the machine.

Sold on the open market, the first Mark I was delivered to the University of Manchester in February 1951 – three years after the Baby’s first test.

What did the Baby’s first program do?

To understand the Manchester Baby’s first program, documentation has thankfully survived, including one key source of insight: Geoff Tootill’s lab notebook. In this book, conservationists have found the actual code that Baby ran.

The general consensus is that the first program - which consisted of 17 instructions - was designed to find the highest proper factor of any given number such as two to the power of eighteen (262,144). The program was written by Kilburn.

After running the programme three times, Kilburn, Tootill and the team celebrated with a trip to the canteen.

IEEE Milestone Awards

There are now over 220 IEEE Milestone Award locations – places of special interest in the historic story of technology’s evolution. The programme has awarded plaques to places such as:

- Nagoya, Japan: Tokaido Shinkansen (Bullet Train), 1964

- Cape Canaveral, USA: Electronic technology for space rocket launches, 1950-1969

- Philadelphia, USA: Birthplace of the barcode, 1948

- Murray Hill, New Jersey, USA: Invention of the first transistor, 1947

- Wall, New Jersey, USA: Detection of radar signals reflected from the moon, 1946

- Bletchley Park, UK: Code-breaking during World War II, 1939-1945