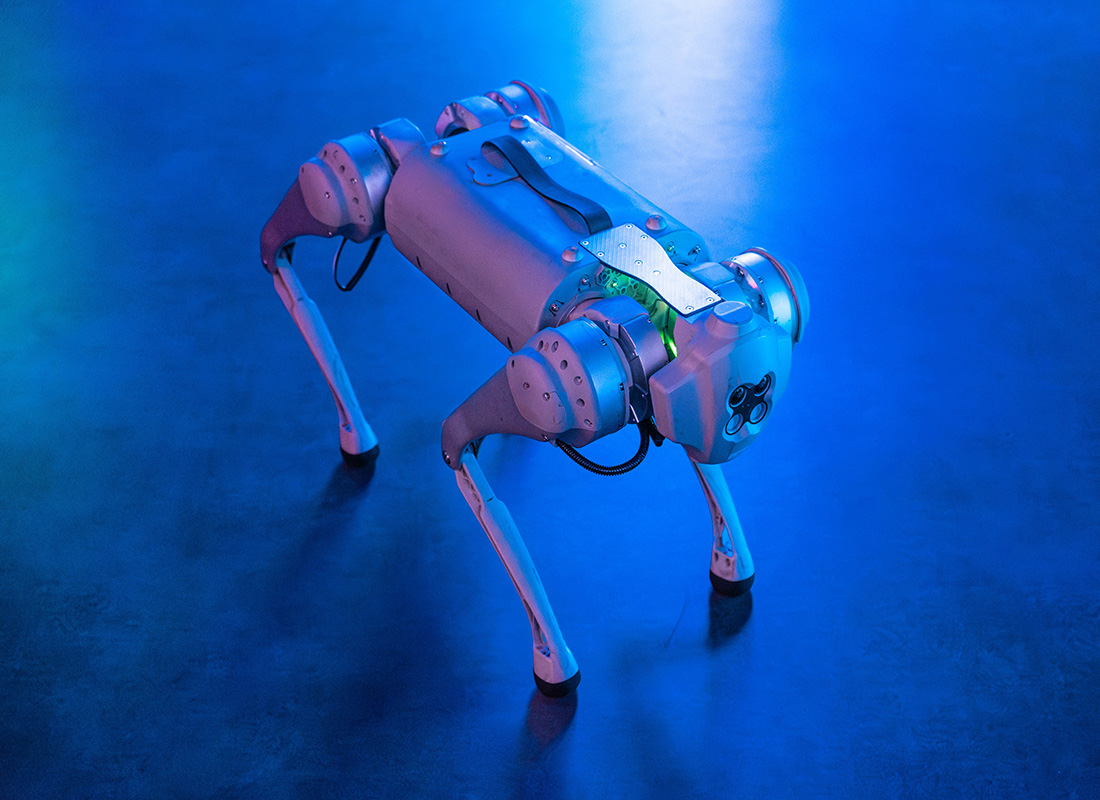

Gustav Metzger photographed in 2008 at a Computer Arts Society event at Somerset House

Gustav Metzger photographed in 2008 at a Computer Arts Society event at Somerset House Photo copyright Catherine Mason.

Throughout more than six decades of artistic endeavor Metzger made pertinent observations on the societal role of the artist though his writings, exhibitions and conferences. He remained always cognisant of the latest technological developments.

Metzger was a Polish Jew who fled Nuremberg with the Kindertransport arriving in the UK in 1939. No doubt due to his early experiences, throughout his life he was particularly aware of the militaristic roots of much of this technology and commented on it in his work. As a child of the 1970s, I feel privileged to have known someone who saw at first hand the Nuremberg Rallies and described to me his experience of witnessing the rise of Nazism.

In 1968 Metzger wrote, ‘[computers] are becoming the most totalitarian tools ever used on society.’ He called for artists not to bury their head in the sand.

During the early years of computer arts activity in Britain, his position challenged those advocates of the utopian possibilities of the coming digital age. He was an active member of the British Society for Social Responsibility in Science and a supporter of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament.

His paper ‘Notes on the Crisis in Technological Art’ described his argument for what he called ‘the most critical topic in technological art - the responsibility of the artist for his material and to society’ by delivering a warning on the role of computers in war and the control of individual freedom.

He was the first editor of PAGE, published from April 1969 and overseen by him until 1972 (and still going today.) When Metzger asked CAS’s co-founder Alan Sutcliffe how big this new journal was to be, Sutcliffe said that there is only enough money to print one page. Well, there is your name, Metzger replied. PAGE was also a pun on the concept of paging (the use of disk memory as a virtual store which had been introduced on the Ferranti Atlas Computer). PAGE featured the work of major British and international computer artists as well as hosting fundamental discussions as to the aims and nature of computer art. The position of Metzger as first editor established from the beginning an association for CAS with the avant-garde.

Metzger’s manifestos (from 1959) contain some of the first references in Britain to the use of computers as possible materials and techniques in art. His 1961 manifesto declared his interest in computer controlled cybernetic systems - he wrote ‘The immediate objective is the creation with the aid of computers, of works of art whose movements are programmed and include “self-regulation”.’ Such concepts incorporating computers for artistic ends were a radical idea and outside the mainstream of British art at the time.

His invention of Auto-destructive art and Auto-creative art aimed to integrate art with the advances of science and technology. He realised computers had amazing potential, although his interest in them was primarily as metaphors.

Auto-destructive art he saw as ‘art to do with rejecting power.’

Gustav Metzger, photograph of Acid Action Painting, 1961

At his Acid Action Painting event in 1961 on the South Bank London, he attacked a seven by 12 foot sheet of nylon with an acid-filled spray gun; the resulting almost instant corrosion being a visceral demonstration of the power of his auto-destructive ideas. (This work was re-created outside the Hayward Gallery in 2006).

In 1962 his lecture on Auto-destructive art at Ealing College of Art influenced student Pete Townsend later to invent auto-destructive rock music with The Who. Metzger’s Destruction in Art symposium of 1966 drew famous artists including Yoko Ono.

In a lecture at the Architectural Association of 1965, he gave details about how computers can be used in sculptures to be auto-destructive.

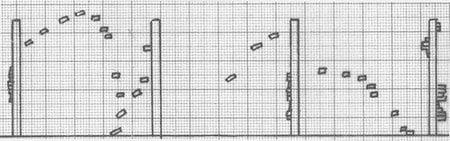

Metzger’s plan for such a work - the computer-controlled public artwork Five Screens with Computer, consisted of five frames made of stainless steel 40ft long, 30ft high and 2ft deep spaced 30ft apart. The computer was to be used in the design, operation and recording of the art work. A drawing for it is reproduced in the Cybernetic Serendipity exhibition publication (seen here).

Five Screens with Computer, 1969

Drawing, black-and-white copy, sketch on graph paper

21 x 29.6 cm

Generali Foundation Collection - Permanent Loan to the Museum der Moderne Salzburg. © Generali Foundation

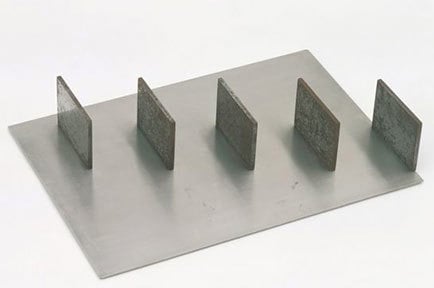

A metal model was exhibited at the CAS show Event One at the Royal College of Art in 1969 and its operation is described in detail in the catalogue (available on the CAS website). Due to the massive scale and prohibitive cost, sadly this project remained unrealised upon his death. The model is now in the Generali Foundation, Vienna which held a retrospective of his work in 2005.

Five Screens with Computer, 1969

Model, Computer-controlled Auto-Destructive monument

Steel, 7.2 x 44.4 x 30.9 cm

Donation by Alan Sutcliffe and Gustav Metzger

Generali Foundation Collection - Permanent Loan to the Museum der Moderne Salzburg

© Generali Foundation, Photo: Werner Kaligofsky

As a special interest group of the British Computer Society, then as now, CAS was able to support pioneers by acting as an international forum for the exchange of ideas between people and by bringing them together for conferences, exhibitions and monthly meetings and occasionally funding.

As early as 1961, Metzger had stated in his manifestos that ‘…the artist may collaborate with scientists, engineers’. Remembering that time, Metzger told me in 2003 that he was ‘excited’ to discover CAS and ‘people coming together’ as he had ‘felt quite isolated.’

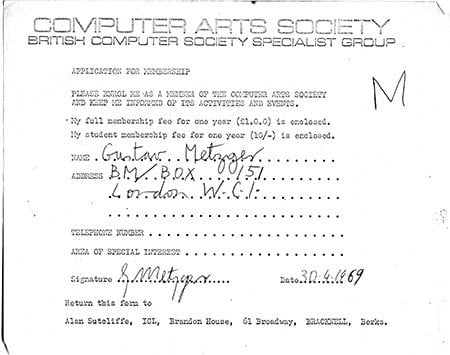

Gustav Metzger’s membership form for the CAS, 1969

The various activities of CAS members demonstrates that, from the beginning, they understood that computing innovations would fundamentally affect humanity. The CAS interdisciplinary approach and stated aim to provide ‘a forum in which artists and scientists [could] jointly work out these implications’ allied with Metzger’s concerns.

For CAS’s first major public exhibition Event One at the Royal College of Art in 1969 he worked with Beverley Rowe, an early member of CAS, from the University of London Computing Centre (and fellow of the BCS), on the Five Screens with Computer project.

As a collaboration of artists and programmers, Event One was to forecast the future activities of CAS. It included a PDP-7 computer with visual display unit, teletype terminals plus graph plotters and a telephone link to an off-site PDP-8 (owned by the musician Peter Zinovieff), all put to creative ends. According to Metzger the combination of fine art with working equipment was nothing less than a ‘revolution in the British art world’ and represented ‘the major collective step forward.’

Other early CAS activities involving Metzger included a three-day event entitled Computers and Education at St Mary’s College, Twickenham (June 1969). This was at a time when very few colleges of education were offering courses in computer programming. Metzger, acting for CAS, led a panel discussion and curated a ‘Computer Art Exhibition’, which included an early working model of Edward Ihnatowicz’s Senster.

Also in 1969 he was also involved with the international symposium Computers and Visual Research in Zagreb, the history of which is documented in Margit Rosen’s book A Little-Known Story About a Movement, a Magazine, and the Computer’s Arrival in Art (2011).

The other side of his creative output - Auto-creative art, incorporated a variety of materials and methods including ink dispersing through glycerine, the use of fibre-optic light to draw lines, water dripping onto a hot plate and liquid crystals moving between physical states to create colours and patterns. These works went on show at Kettles Yard Gallery, University of Cambridge, in 2014.

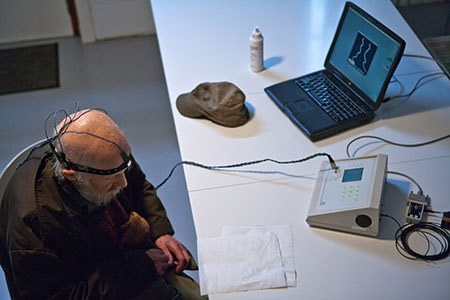

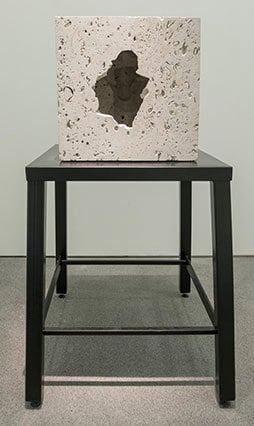

CAS was able to fund (along with the Arts Council) Metzger’s collaboration with London Fieldworks (Bruce Gilchrist and Jo Joelson) in 2012. This was entitled NULL OBJECT: Gustav Metzger thinks about nothing. A computer-brain interface linked with industrial manufacturing technology resulted in the creation of a 3D sculptural object made of Portland stone. Using bespoke software, data from EEG readings of Metzger’s brainwaves, as he attempted to think about nothing, was translated into instructions for a manufacturing robot, which carved out the shapes from the interior of a 50cm cube of fossilised stone to create a void space. (pictured below)

Gustav thinking about nothing by London Fieldworks 2012

With Metzger’s typically thoughtful critical stance, NULL OBJECT presented a challenge to the present climate of technological evolution and increasing cybernetic augmentation. He offered an alternative model for a creative, non-invasive interface between body, mind and machine. (See also accompanying book of the same name).

Null Object 1 by Jon Barraclough 2014 photographed as part of The Negligent Eye at Bluecoat Gallery

London Fieldworks along with curator Bronac Ferran were great supporters of Metzger during his later years.

Metzger continued to be involved with CAS activities until very recently. See him in conversation with our Chairman Nick Lambert at the ICA in 2014, discussing Cybernetic Serendipity.

His work is in the collection of the Tate.

See also the excellent Arts Council produced DVD Pioneers in Art & Science: Metzger (Dir. Ken McMullen, 2004).

Metzger said in 2012, ‘I’ve always opposed two things in art: celebrity and commercialisation.’ That he sought neither probably made his life more difficult at times. Though he was well-known and appreciated by those colleagues in the art world who matter. Ultimately his strong integrity and adherence to his ideals is admirable and remains a tribute to him. He will be greatly missed.